Facts About The Legendary Gladiator Spartacus

111 BC was a completely different time in human history. In the Third Servile War, Spartacus was a Thracian gladiator who was one of the escaped slaves. Upon escaping captivity, he influenced an enormous slave uprising against the Roman Republic. We don’t know much about his life besides what happened in the war, but it is generally agreed upon that he turned into a successful military leader.

Let’s take a look back to see how one man went from an enslaved gladiator to one of the most revered war heroes in ancient history.

Roman Army Member

Initially, Spartacus was a member of the Roman army. Yet, he didn’t particularly like being ordered what to do or risking his life for something he didn’t care about. So he fled the army to live on his own terms.

In addition, some historians even argue that Spartacus was a Roman auxiliary officer, meaning he would have volunteered to enlist. After illegally leaving the army, he was eventually captured and sold into slavery as punishment for deserting. His days as a gladiator were about to begin.

Little Else Is Known About His Early Life

Up until his time in the Roman army, almost nothing is known about Spartacus’s early life. Even what is known is better described as widely understood to be true, rather than concretely confirmed.

He was likely born in Thrace, which was situated in what is now the Balkan region of Eastern Europe. As far his pre-military life that led to his enslavement and rebellion goes, there are far more blanks than information to fill them.

The “I Am Spartacus” Moment Never Happened

Easily the most famous moment from Stanley Kubrick’s 1960 film about Spartacus’s life has Spartacus identify himself before his Roman captors after a failed battle, only for him to be touched and stunned by his troops’ reaction. After he calls out, “I am Spartacus,” the others echo him until it’s unclear to the Romans who Spartacus actually was.

However, this inspirational moment, where his troops were just as willing to sacrifice themselves for his cause as Spartacus himself was purely invented for the script. By the time he fought his final battle, there was no confusion among the Romans about Spartacus’s identity. He also likely died in combat.

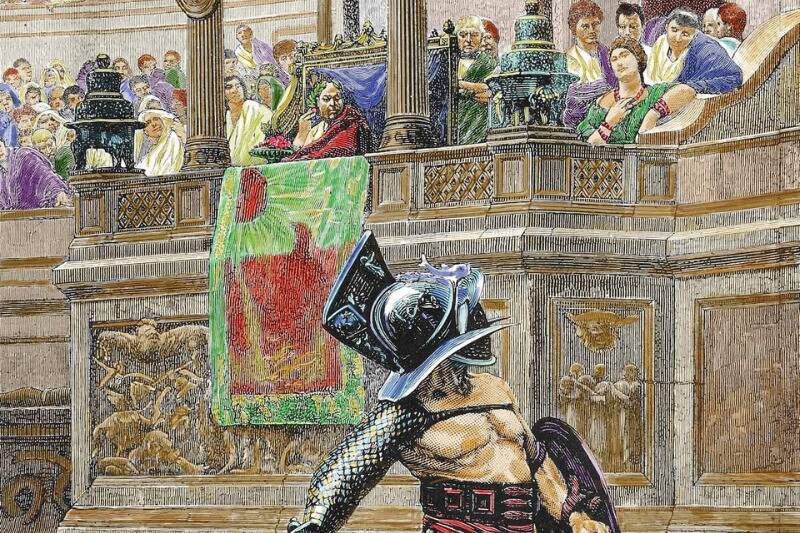

No Way Out Of Gladiator ‘School’

Spartacus was purchased by a man named Lentulus Batiatus, who was quick to enroll the former soldier in the gladiator school in Capua, a school that Batiatus owned himself. This school that Spartacus was forced into was notorious for its harsh treatment of its slaves, with Batiatus being particularly ruthless.

It’s believed that the treatment of the Gladiators by the trainers and Batiatus is one of the key reasons that Spartacus made an attempt to escape slavery.

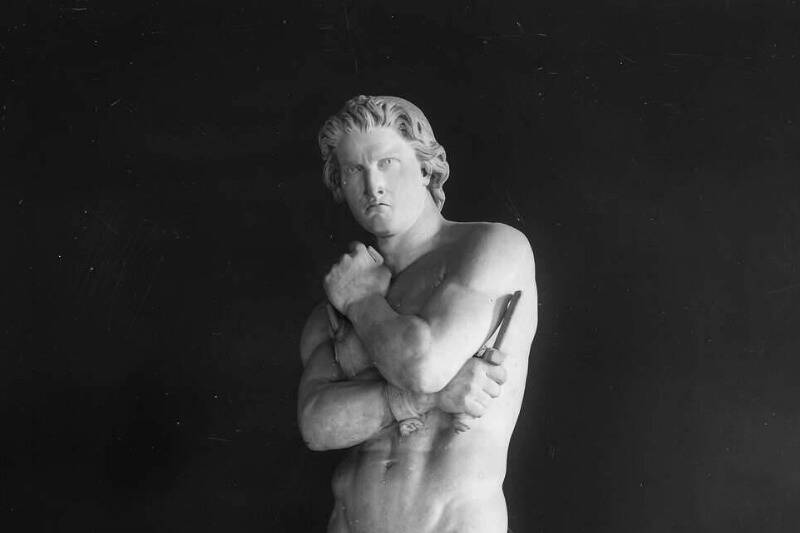

Got Put In Heavyweight Fighting

Under Batiatus, Spartacus was trained to fight as a heavyweight gladiator called murmillones. These were a type of gladiator during the Roman Imperial Age, which was established to replace the earlier Gallus, named after the warrior of Gaul.

Typically, these warriors were armed with a gladius, or sword, a shield, leather belt, along with other small pieces of armor. Their fighting style was for men with large builds that could wield a sword, shield, and wear a heavy helmet. They would also typically fight against other murmillones.

Spartacus’s Revolt Started With An Ambitious Breakout

After Spartacus was trained as a murmillone, it didn’t appear to be long before he started convincing his fellow gladiators to work together rather than harm each other. Since his fight record or even descriptions of his status in the gladiatorial games weren’t known, he may never have actually made it to the Colosseum.

Instead, National Geographic reported that he and about 70 other gladiators escaped from Batiatus’s clutches. According to Live Science, they did this by force and were armed with weapons either procured or fashioned from their oppressor’s kitchen items.

Establishing Themselves At Mount Vesuvius

It’s common knowledge that Mt. Vesuvius is a volcano that erupted in 79 AD, obliterating the nearby town of Pompeii. Around 100 years before the eruption, the volcano was used as a strategic hideout by Spartacus and his initial band of followers to escape the Roman legions that were on their tails.

At the time, the Romans knew that they were up in the mountain and had plans to enact a siege in an attempt to starve out the rebels into submission.

We Know What We Do About Spartacus Mostly From Plutarch

Most of what we know about Spartacus and his uprising are from the writings of a man named Plutarch. An ancient historian, Plutarch roamed throughout Greece and the Roman Empire around 70 AD. During his travels, he wrote extensively about Alexander the Great, the Spartans, and Spartacus.

According to Plutarch, Spartacus’ wife, prophetess, had a dream of Spartacus sleeping with a snake on his face not long after his capture in Rome. She took this vision as “the sign of a great and terrifying force which would attend him to [an]…issue.” A great and terrifying force was exactly what he was.

Even The Name Of Spartacus’s Wife Remains Unknown

Although Plutarch described Spartacus’s wife as a prophetess of Dionysus (or Bacchus in Rome) and she was believed to have also been born in Thrace, there’s little else known about her besides the fact that she left with him when he and the 70 other gladiators escaped from Batiatus.

She was named Varinia in the Stanley Kubrick film, but this was also an invention of the script. In reality, Live Science noted that this woman’s name was lost to history. If Plutarch knew it, he didn’t mention it.

Big Mistake By The Roman Government

One of the main reasons that Spartacus and his fellow slave-gladiator revolt was so successful was mostly because of the Roman government. At the beginning of the revolt, the Romans didn’t see Spartacus and his army as nothing more than a rag-tag group of hooligans that were no real threat at all.

With this mindset, they refused to send main military forces to put it down, but instead, assumed that the police would be able to handle it. They were sorely wrong.

Assembling An Army

After his initial escape from the gladiator school and establishing himself at Mount Vesuvius, Spartacus and his men began recruiting other slaves and soldiers to their cause. Two years later, he was at the head of an army of more than 90,000.

During this time, Rome sent several military forces to defeat Spartacus, but to no avail. The first commander to take them on was praetor Claudius Glaber, who was defeated after Spartacus and his men escaped using vines on the side of Mount Vesuvius to attack from behind. Spartacus then went on to defeat a slew of other forces Rome threw at him.

Even With Glaber’s Involvement, Rome Wasn’t Serious

Part of the reason the Roman government didn’t take Spartacus seriously was that the republic was tied up in other conflicts in Crete, southeastern Europe, and what is now Spain. According to Live Science, this was reflected in the forces Claudius Glaber was able to amass when he was dispatched.

Glaber’s second-in-command was a man named Publius Valerius, and a quote from the second-century writer Appian obtained by Live Science makes it clear that they didn’t have much to work with. As Appian wrote, they “did not command the regular citizen army of legions, but rather whatever forces they could hastily conscript on the spot.”

His Campaigns Made It As Far As Gaul

While the Romans did eventually take Spartacus’s rebellion seriously, he and the 90,000 to 100,000 troops he was able to amass had an impressive string of successes while they were dragging their feet. As mentioned, they even proved a formidable foe when the republic dedicated resources to fighting them.

Julius Caesar famously campaigned in Gaul later, which speaks to how impressive Spartacus’s forces were to be able to make it that far. Gaul made up a section of what is now modern-day France.

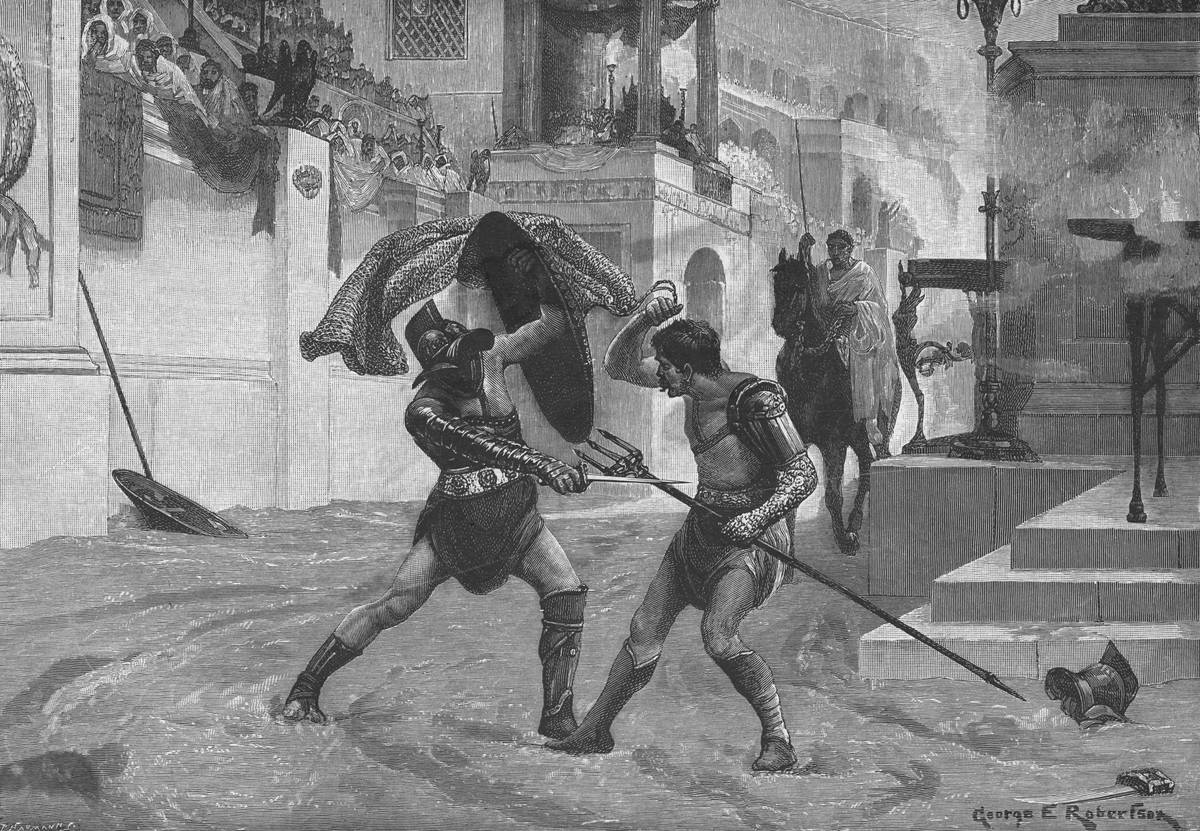

He Made An Unfortunate Deal With Pirates

Since Spartacus’ plan to march across the Alps didn’t work out, he tried to make it to the Italian coast to sail to Sicily. Unfortunately, he made the wrong deal with a group of Silician pirates from Asia Minor that had plundered the Mediterranean coastline for decades and had their eye on Sicily as well.

Spartacus made it to the Strait of Messina, expecting to be ferried by the pirates to Sicily. However, the pirates never showed up, putting Spartacus between a rock and a hard place.

The Final Battle

After the pirates had betrayed him and his men, Spartacus came face-to-face with Marcus Licinius Crassus, one of Rome’s richest and influential political figures. Crassus brought with him eight legions, and to prove a point, killed every tenth man in the two units who had previously been defeated by Spartacus, to show that defeat would not be tolerated.

Spartacus offered to make a peace treaty but was rejected. Spartacus and Crassus met on the battlefield in 71BC. Crassus’ army overwhelmed Spartacus’ troops, resulting in his death, and the end of the rebellion.

How Crassus Won

Judging by evidence uncovered by researchers from the University of Kentucky and described by Smithsonian Magazine, Spartacus and Crassus’s historic battle took place in what is now the Italian region of Calabria. Indeed, that evidence is also a clue to the key to Crassus’s victory.

Although Spartacus fell in a decisive battle that saw tens of thousands slaughtered, Crassus had an advantage before the battle even started. That’s because Crassus trapped Spartacus’s forces by having a stone wall built first. Although some evidence shows that Spartacus’s troops knocked through the wall, that was clearly insufficient to win the day.

His Body Was Never Found

After Spartacus’ death on the battlefield on the banks of the Silarus, now known as the Sele River, his body was never found, although some say differently. The battle had been so violent and bloody that it almost seemed impossible that anyone would have been able to identify him, especially considering that the Romans had won.

And since there was no way to tell exactly how many soldiers had died on each side, it’s estimated that 36,000 people in total lost their lives.

His Intentions Are Still Unclear

According to historian and author Barry Strauss, Spartacus and his army were a bit more controversial than what we have been led to believe by Hollywood. For example, while he and his army were supposedly fighting for their freedom, it’s often overlooked that they were also pillaging innocent people’s homes on their marches up and down Italy.

Furthermore, it’s still debated over what Spartacus’ motivations were behind his revolt, with many historians claiming it was unlikely to put an end to slavery in the region.

His Army Grew From Knowing Where To Go

Although the Roman households Spartacus pillaged along what is now the Italian countryside certainly didn’t appreciate his presence, many of them were likely outnumbered by the enslaved people who would end up joining his cause. That was part of the reason why he chose the locations to pillage that he did.

As Live Science explained, these rural areas might as well have been gold mines for Spartacus. Not only was the Roman Republic’s territory too vast for these areas to be adequately defended, but there was a high proportion of enslaved people among their populations.

Spartacus Was Uniquely Fair To His Troops

Although Spartacus’s story likely began with his own desertion from the Roman army, he had an admirable and ingenious way to prevent similar abandonment among his ranks. Regardless of what the motivations of his rebellion ultimately were, his attitude toward troop morale reflected his ethos.

According to Live Science, that’s because Spartacus insisted on dividing the spoils from his victories and pillages equally among his forces. Not only did that help immensely in recruited enslaved people who would have felt they had nothing to lose and a lot to gain, but it also helped keep the men he had loyal to him.

Cassius Punished The Remainder Of Spartacus’ Army

After the majority of Spartacus’ army had been annihilated by Cassius’ forces, there were only around 6,000 of them left alive. Of course, there was no way that Cassius was going to let them go, and instead, sentenced them to horrible deaths.

All of the remaining men of the rebellion were ordered to die by crucifixion, one of the harshest forms of capital punishment established by the Roman Empire. All 6,000 survivors were then crucified along the Appian Way between Rome and Capua as a sign to all other slaves that might have a similar idea.

The Rebels Split Their Forces

At one point during the fighting, Spartacus and his Lieutenant Crixus parted ways, although the reason why isn’t exactly clear to historians. One possible reason is that the split could have been a tactical maneuver by the two leaders of the army to confuse the Romans.

On the other hand, some claim that Crixus left Spartacus in order to pillage the Roman countryside on the way to Rome. Either way, it was detrimental to the war effort with Crixus taking around 30,000 soldiers with him.

The Split Of The Army Proved To Be Fatal

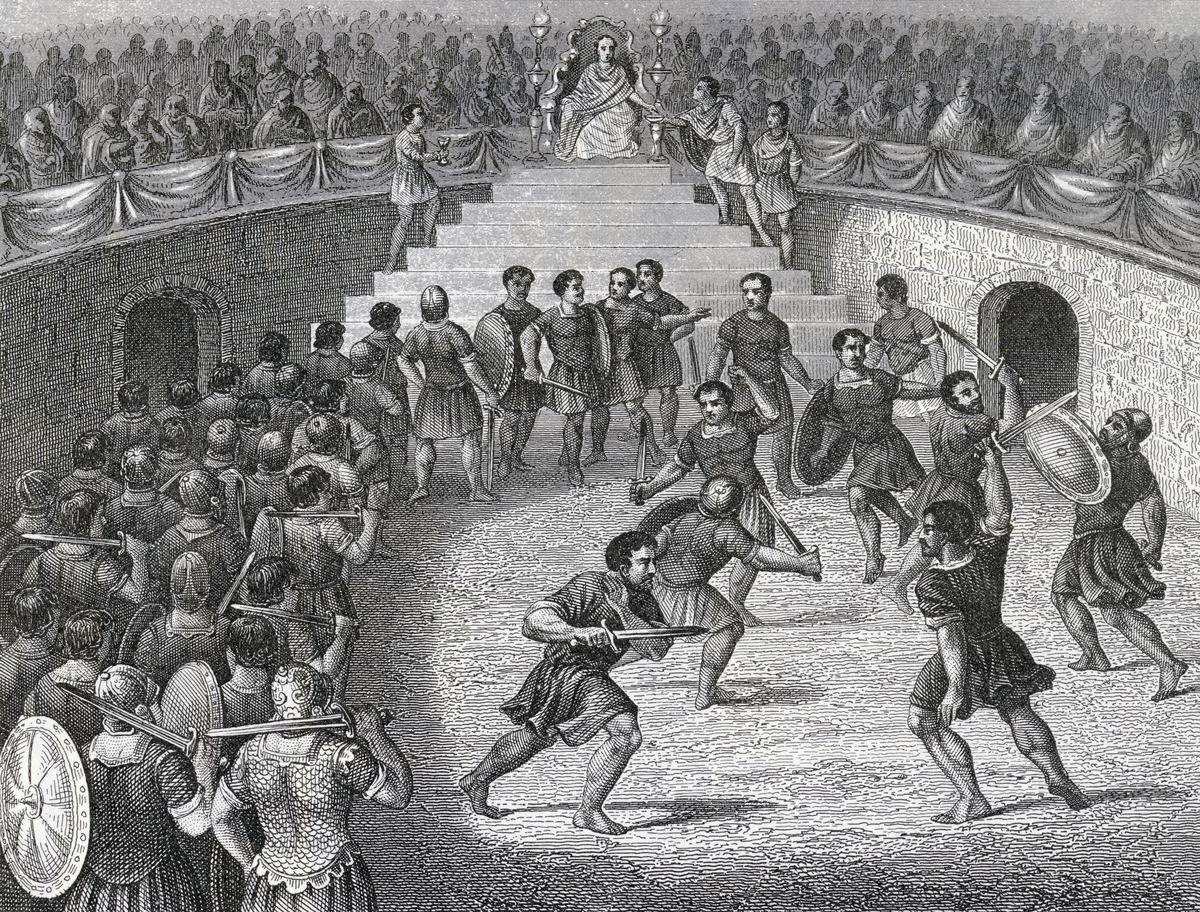

After Crixus left Spartacus with around 30,000 of the army’s men, Crixus and those who followed him were attacked and defeated by the Roman Army. Upon hearing the death of his closest friend, Spartacus took his revenge by sacrificing 300 of his Roman captives.

However, he did so in a rather poetic yet gruesome fashion. Instead of just executing the soldiers, Spartacus had a version of his own gladiatorial games in which he forced the Roman soldiers to fight to the death.

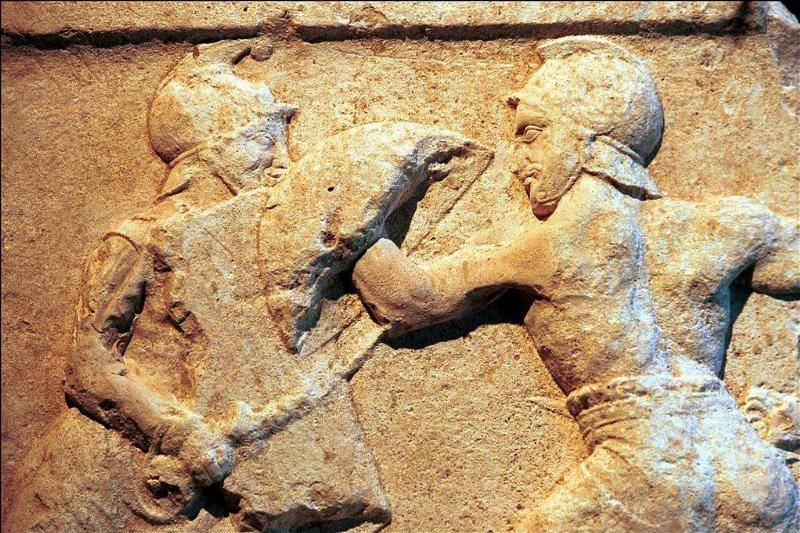

Fights Weren’t Always To The Death

Modern popular culture may depict gladiatorial battles as a free-for-all with the last man standing as the victor, in reality, many of the fights followed strict regulations. Gladiators were often matched according to their size and skill with referees on hand to stop a fight if someone becomes seriously wounded. In some cases, both gladiators were able to leave the Colosseum with honor if they put on a good show.

Furthermore, gladiators were an investment and cost a lot of money to house, train, and feed, which meant the last thing promoters wanted to see was them killed. Of course, many did die, with historians estimating between one-in-five or one-in-ten fights resulting in death.

Life Didn’t Get Easier For Enslaved People After Spartacus

Although Spartacus has gone down in history as an inspirational figure for resisting oppression, his legacy in the coming Roman Empire was far more muted. Those hoping to hear about any reforms to the institution of slavery in Rome at the time are bound to be disappointed.

As Frederick B. Chary wrote for EBSCO, the only lesson the Roman government learned from Spartacus’s uprising was how dangerous slave revolts could be. As such, the administration imposed tighter controls on gladiators and other ensalved residents to ensure the third and most famous Servile War wouldn’t be followed by a fourth.

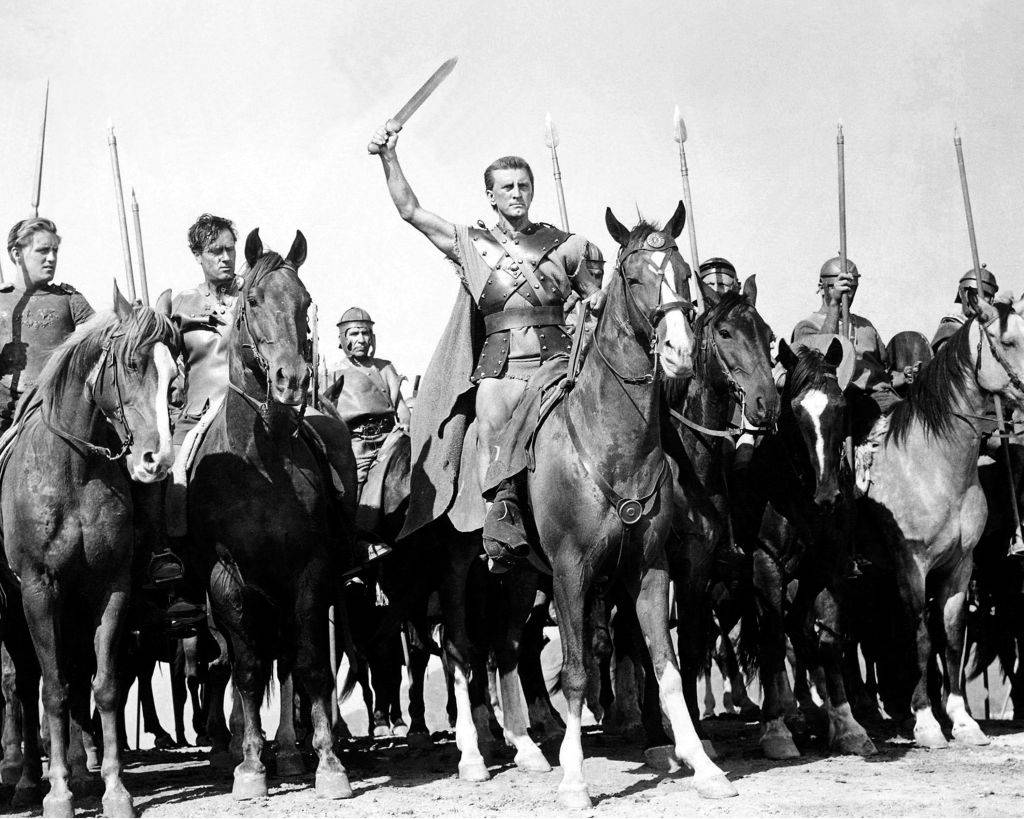

Hollywood Loves Him

One of the best-known film adaptations of Spartacus’ life is director Stanley Kubrick’s 1960 film Spartacus. Starring Kirk Douglas and based on Howard Fast’s novel of the same name, the film went on to win four Academy Awards and became the most profitable film in Universal Studios’ history.

The story of Spartacus has also been adapted for television with over-dramatized shows such as Spartacus on Starz premium cable network. Surely, we will be seeing Spartacus on the big screen again eventually.

Spartacus Left Behind Quite The Legacy

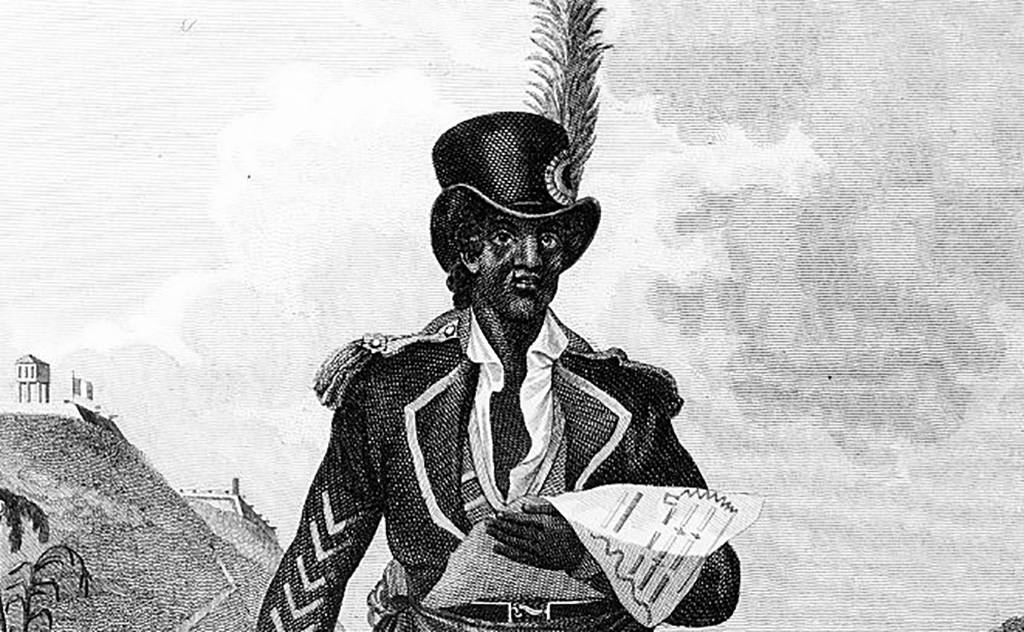

Spartacus’s uprising against Rome has inspired other oppressed individuals to do the same. For example, Toussaint L’Ouverture, a leader of the slave revolt that led to the independence of Haiti, has been called the “Black Spartacus.”

Furthermore, Adam Weishaupt, the founder of the Bavarian Illuminati, often referred to himself as Spartacus. Karl Marx, one of the founders of communism, has cited Spartacus as one of his heroes, describing him as “the most splendid fellow in the whole of ancient history.”