Historical Photos That Give Us A Rare Look At The Chernobyl Disaster, Past And Present

The Chernobyl nuclear disaster looms large in popular culture. It stands as a potent message about the destructive potential of nuclear power, a symbol of Soviet dysfunction, and is to this day one of the worst nuclear disasters in history.

But context is everything. Chernobyl was more than a nuclear power plant, it was the site of a flourishing town — and the effects of the disaster are still being felt today, decades later.

The power plant was located in Pripyat, Ukraine.

Pripyat was a master-planned Soviet city, built in 1970 — less than two decades before the disaster that would force it to be abandoned.

At the time of the disaster, about 50,000 people lived in Pripyat, and it was a fully modern city, complete with schools, hospitals, parks, and an amusement park that was under construction.

The disaster occurred during a late-night safety test.

Technicians at Chernobyl wanted to determine how long the plant’s turbines could provide power after a shutdown. Owing to a combination of factors — operator error, poor reactor design, and unsafe procedures — the test went catastrophically wrong.

At 1:23 AM on April 26, 1986, an uncontrolled reaction triggered a series of massive explosions that blew the 1,200 ton teactor lid off, exposing Chernobyl’s radioactive core.

A fire made things even worse.

The effects of the initial explosions, and subsequent fire, can be seen here in this aerial shot. The explosions started a fire, which raged over the exposed radioactive core, releasing various radioactive isotopes into the air.

Firefighters raced to the scene of the emergency, but believed it was just a regular fire. They were unaware of the extreme radiation levels, and most weren’t wearing proper protective gear.

Residents were unaware that a disaster was happening.

The residential tower blocks seen here were just a couple of miles from the nuclear power plant, but despite this proximity, most locals were kept in the dark.

In fact, it wasn’t until 36 hours after things went haywire that residents were fully evacuated — a delay that no doubt made things worse for the citizens of Pripyat.

A radioactive mass formed under the destroyed reactor.

The mass of molten nuclear fuel mixed with reactor materials to form a lump known as the “Elephant’s Foot.”

The photographer shown here is wearing proper protective gear as he photographs the mass, but it’s still a risky proposition. Standing near it for even a minute in 1986 could cause a fatal dose of radiation. In the decades since, its radiation levels have decreased, but it remains dangerous to this day.

It was devastating for the people of Pripyat.

Many nuclear plant employees and first responders died within days or weeks, but even those who weren’t directly in the area of Chernobyl were gravely affected.

31 people died immediately from the explosion, somewhere between a few dozen to a few hundred died within four years, and the longer-term effects have likely killed thousands more.

The Soviets only acknowledged the disaster two days later.

Officials did their best to keep the disaster under wraps, but it was a secret that was too big to keep. Two days later, technicians at a Swedish nuclear power plant noticed an abnormal spike in radiation levels.

This prompted the Soviet Union to acknowledge that a nuclear accident had occurred. With this news, nearby countries immediately responded.

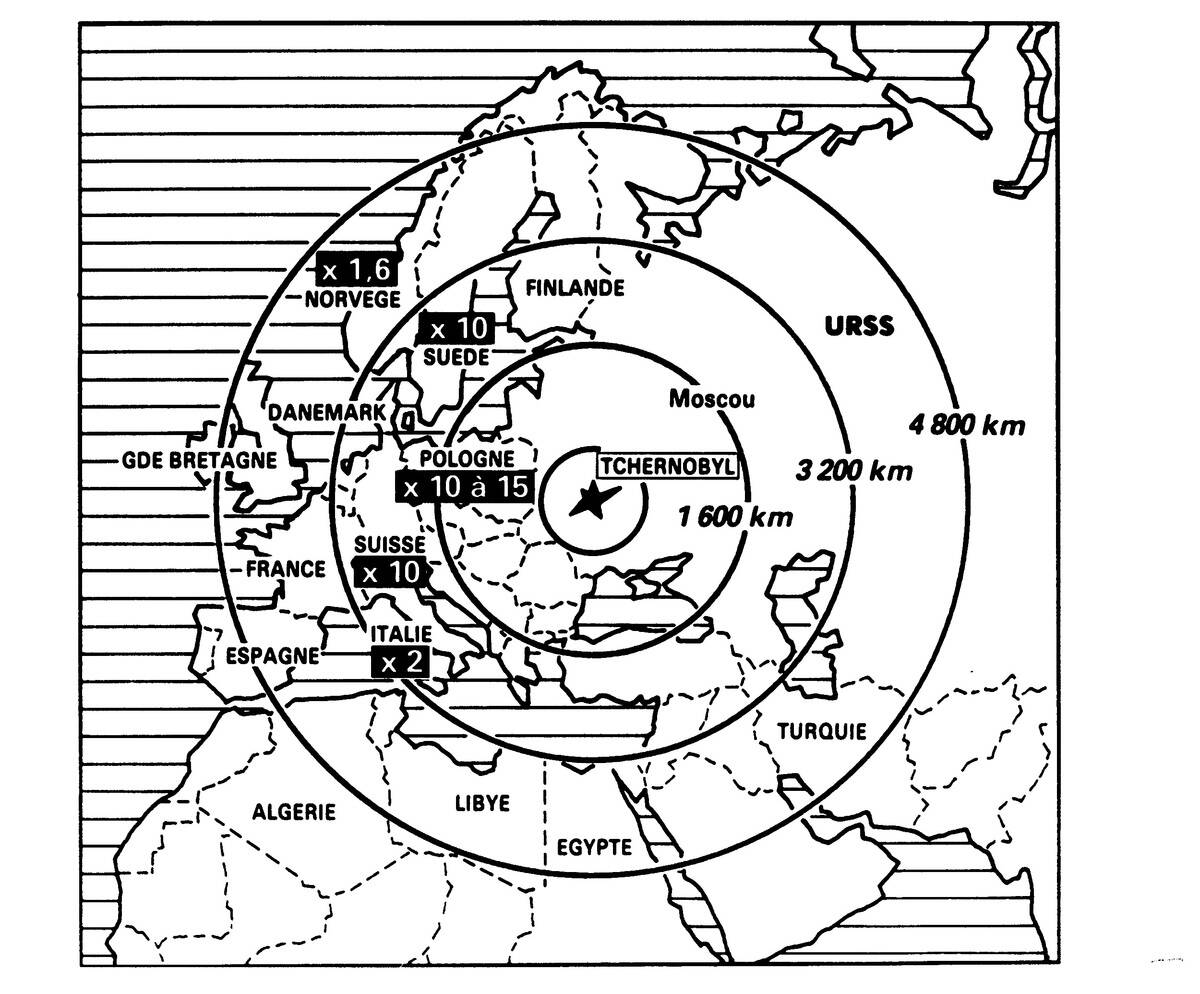

The radiation spread far beyond Pripyat.

This illustration shows the effects of the radiation spread following the disaster. Most of Europe, along with parts of Africa and the Middle East, were affected.

While there have been other nuclear disasters, Chernobyl stands alone as the worst nuclear accident in history. It’s classified as a Level 7 event on the International Nuclear Event Scale, which is the highest possible rating.

Other countries did their own cleanup.

This image out of West Germany, taken a few weeks after the disaster, shows some of the precautions taken in the immediate aftermath. Customs officials closely scanned all goods coming from Eastern Europe, while wearing full protective gear.

The disaster triggered a flashpoint in relations between the Soviet Union and the West, as the generally secretive Soviets were unable to hide the magnitude of the disaster.

Tensions ran very high.

Following an unprecedented nuclear disaster with potentially devastating levels of radiation leaking over an area populated by millions, diplomatic tensions understandably ran high.

As the Soviets scrambled to not only clean up at Pripyat but also to control the narrative, European countries tightened up border security to ensure that potentially radioactive imports were flagged.

Cleanup was a top to bottom affair.

West Germany, with its relative proximity to Chernobyl, was understandably very concerned in the immediate aftermath of the disaster.

This image shows workers digging sand out of a playground because it was potentially radioactive. They had to do this at all potentially affected playgrounds and swap in clean sand.

It prompted anti-nuclear protests.

This scene in Frankfurt, Germany, just a few days after the Chernobyl disaster, captures the prevailing sentiment of the time.

The world had already been living under the threat of nuclear war for decades due to the Cold War, and the Chernobyl incident — though it was an accident — still served as a powerful reminder of the potential of nuclear destruction.

At Pripyat, the cleanup was significant.

It’s difficult to overstate the challenges faced at Pripyat. Cleanup crews were dealing with an unprecedented disaster and a cagey, uncooperative central government in Moscow.

With the town’s population fully evacuated, an exclusion zone was set up. The only people in the largely deserted town were cleanup crews and Soviet officials.

They worked to contain the reactor.

Because of the spread of radiation, it’s effectively impossible to “clean up” a site like Chernobyl so there’s no radiation left. The only option is to contain it.

Crews built a massive containment structure over the affected reactor, Reactor 4, with the aim of preventing the release of further radiation. It was a quick fix, and the hastily-constructed “sarcophagus” would eventually pose its own set of problems.

Pripyat was left to rot away.

A city of 50,000 people is bound to have plenty of buildings and features, and while Pripyat remains abandoned to this day, much of its structures still remain.

The former citizens of Pripyat would never live there again, and were relocated to safer areas around the Soviet Union.

Most people weren’t able to gather their belongings.

In the chaotic aftermath of the disaster, officials told evacuating citizens that they’d be allowed to return within a few days.

Of course, the disaster was much worse than expected, and Pripyat would never be inhabited again. Even though people were forced to abandon their belongings, these belongings would have been contaminated with radiation anyway.

Modern-day Pripyat is an eerie place.

It isn’t just buildings that remain, but also much of the equipment that was used in the immediate aftermath.

This image shows a couple of Soviet helicopters that were used to assess the damage. After landing in this field, they never took off again.

Crops were destroyed.

Ukraine is known as Europe’s breadbasket, and vast areas of the country are covered with fertile farmland.

Of course, the wide-ranging effects of radioactivity from the Chernobyl disaster made many crops unsafe. This farmer isn’t harvesting vegetables, but is rather crushing and burying them.

The sarcophagus needed to be replaced.

The first iteration of the sarcophagus to contained the affected reactor was a product of rushed construction, and wasn’t really built to last long-term.

In the 2010s, the crumbling sarcophagus was replaced with a new structure — one that should hopefully withstand the passage of time a little better.

It’s an illicit tourist destination.

While the area is officially an exclusion zone, lax security in the final days of the Soviet Union, and in the years to follow, meant that Pripyat was a relatively easy site to explore for urban explorers.

Because the city was abandoned within just a few hours, most buildings were left as they stood.

There are still reactors on site.

The accident occurred at Reactor 4, which means that there were three other reactors that were unaffected. While it immediately became untenable to maintain a nuclear plant on site, decommissioning a nuclear plant is an in-depth project.

This image from 2015 — nearly 30 years since the disaster — shows a technician at Reactor 2, still involved in the long and complex decommissioning process.

The memories remain.

Every year, those affected by the disaster — whether they’re former residents of Pripyat or the friends and loved ones of those killed in the disaster — gather to pay tribute.

These solemn ceremonies often involve the laying of flowers or wreaths at various memorials that were built to honor those who were lost.

Life has returned to the exclusion zone.

In a sense, life never really left — in fact, wildlife flourished in the newly abandoned city, even if said wildlife was affected by radiation.

This image from 2018 shows a volunteer from the Clean Futures Fund (CFF), holding a stray puppy outside of an improvised pet shelter near Chernobyl. The group has been working to take care of the stray dogs in the area.

Legitimate tourism is picking up.

Pripyat and Chernobyl had been urban exploration hotspots for years, but in the 2010s, the area started opening up to approved tours.

These supervised tours allow curious visitors to get within a couple hundred feet of the destroyed reactor and its newly-built sarcophagus structure.

Pripyat wasn’t the only affected city.

This simple but powerful symbolic memorial has tourists at the Chernobyl exclusion zone walking between signs — each one representing a village or city that was evacuated.

Symbols like this, along with the memorials for those who were killed, show the human cost of the Chernobyl disaster.

It’s still a ghost town.

While radiation levels have gradually gone down and safety has improved with the new sarcophagus, this doesn’t mean that Pripyat is going to experience a rebirth anytime zoon.

Sanctioned tours take tourists around approved areas, but most of the city’s structures still look like this supermarket — abandoned buildings that have been rotting in place for more than three decades.

The invasion of Ukraine complicated matters.

The complex history of Russian-Ukrainian relations has been tested in recent years, with Russian incursions into its former territory.

This 2023 image shows Ukrainian National Guard members laying flowers at a Chernobyl memorial. At the time, they were also actively involved in fighting against the Russian invasion.

Former residents have been allowed to return at times.

They’re not allowed to move back into their former dwellings, of course, but brief visits to Chernobyl are generally regarded as safe.

This image shows a man named Anatolij in 2001. His thoughtful expression is likely due to the fact that he’s standing in the Pripyat home he was forced to abandon in 1986.

Many people are still affected.

This photo, taken during the same 2001 visit that brought Anatolij back to Pripyat, shows a family standing in their former apartment.

The visit was especially poignant for them, because one of their family members died as a side effect of the radiation.

It’s a sombre reminder of the destructive power of radiation.

The atomic attacks on Hiroshima and Nagasaki in 1945 showed the world the true power of this form of energy. But events like Chernobyl — and to a lesser extent, Three Mile Island – showed the public that radioactive destruction can also come as the result of a catastrophic mistake.

Chernobyl won’t be safe to live in within the lifetime of anyone currently living, and its ruins stand as a grim monument.