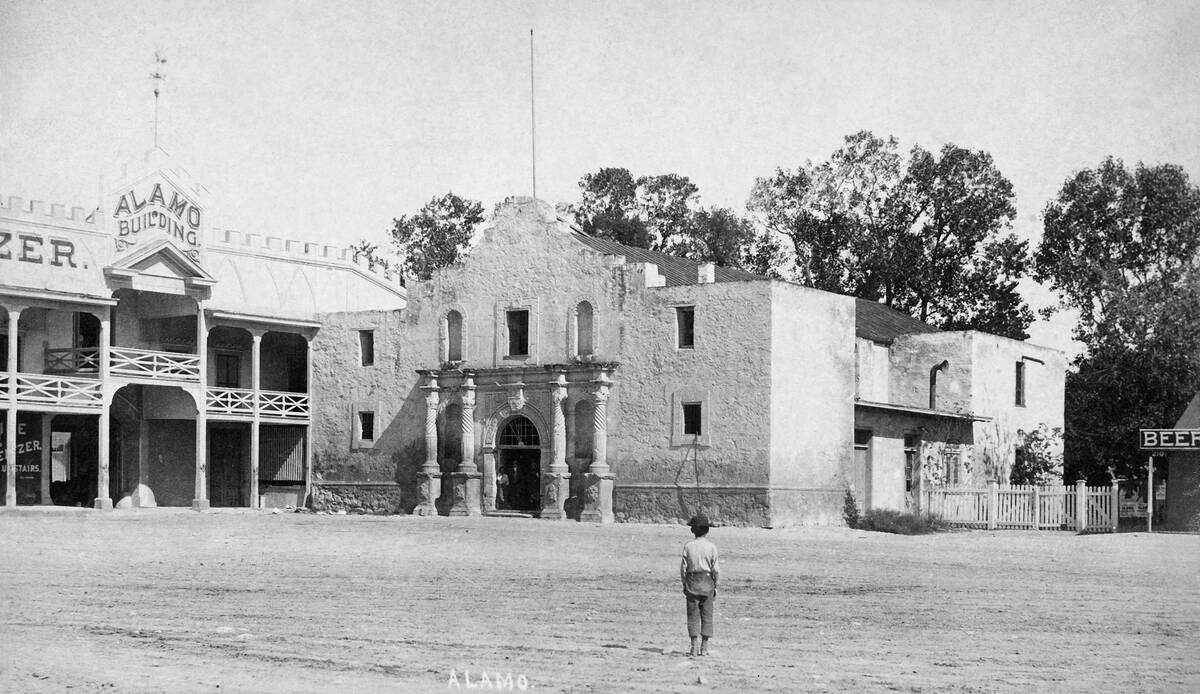

Rare Historical Photos Bring The Battle Of The Alamo To Life Like Never Before

There is no landmark more important to Texans than the Alamo and for good reason. What began as a religious mission evolved into an enduring symbol of hard-won independence that no Texan worth their salt will ever forget.

While the exploits of the brave volunteers who gave their lives at the Alamo are forever enshrined in history, this makeshift fortress’s symbolic value shined through the hardships of the later Mexican-American War that carried Texas to the end of its long, bloody road to American statehood.

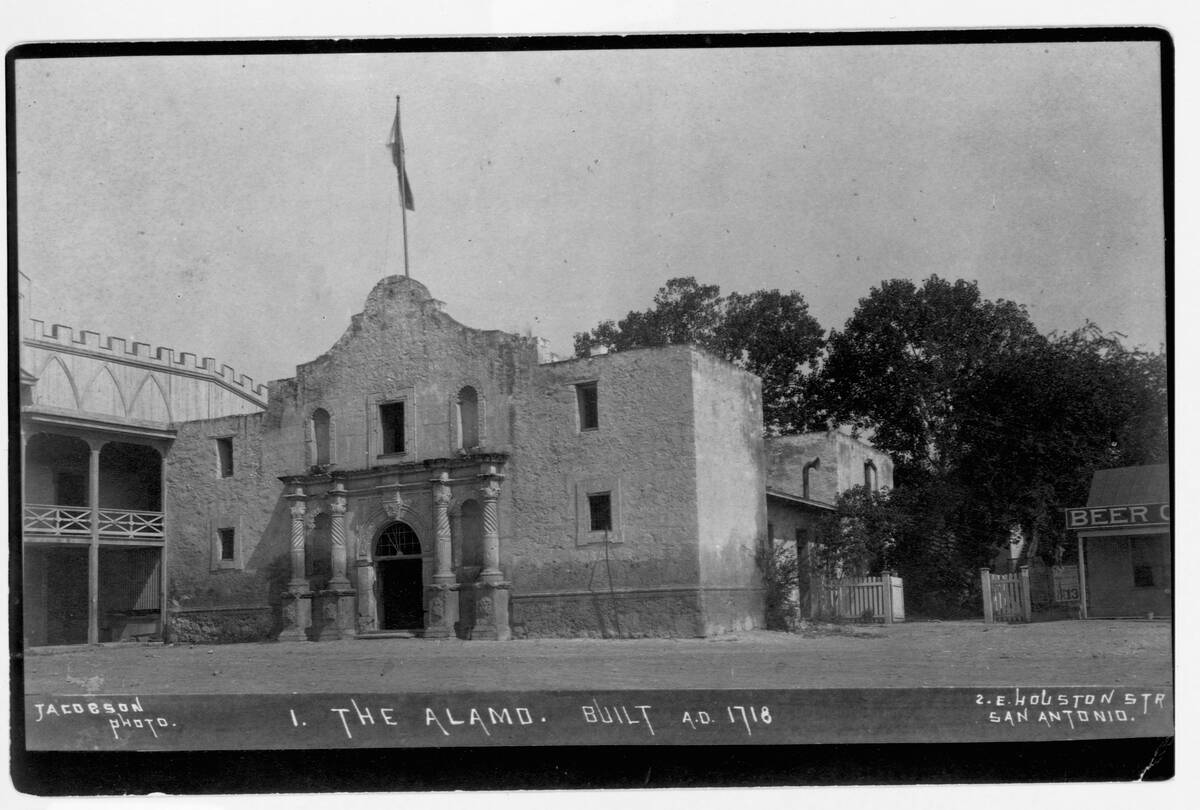

The Alamo’s Spanish Origins

Long before anyone called it the Alamo, this structure was known as Mission San Antonio de Valero and it was named after the Portuguese-born saint Anthony of Padua.

Although it’s nestled in the Texan city of San Antonio today, the original settlement it was constructed near in 1718 was called San Fernando de Béxar.

The Spanish Empire Changes Its Purpose

After housing missionaries and the Native Americans they converted to Christianity for about 70 years, Spanish authorities took a secular eye to multiple missions in the region.

This meant the land they used would be distributed among the area’s residents but those same authorities had their own plans for a structure as solid as Mission San Antonio de Valero.

The Alamo Gets Its Name

Throughout the early 19th Century, Spanish soldiers stationed at the mission started calling it “El Alamo,” which was a reference to both the grove of cottonwood trees surrounding it and the Mexican town of Alamo de Parras.

By 1821, the troops stationed there would be independently Mexican, as the nation’s war of independence from Spain would end on September 27.

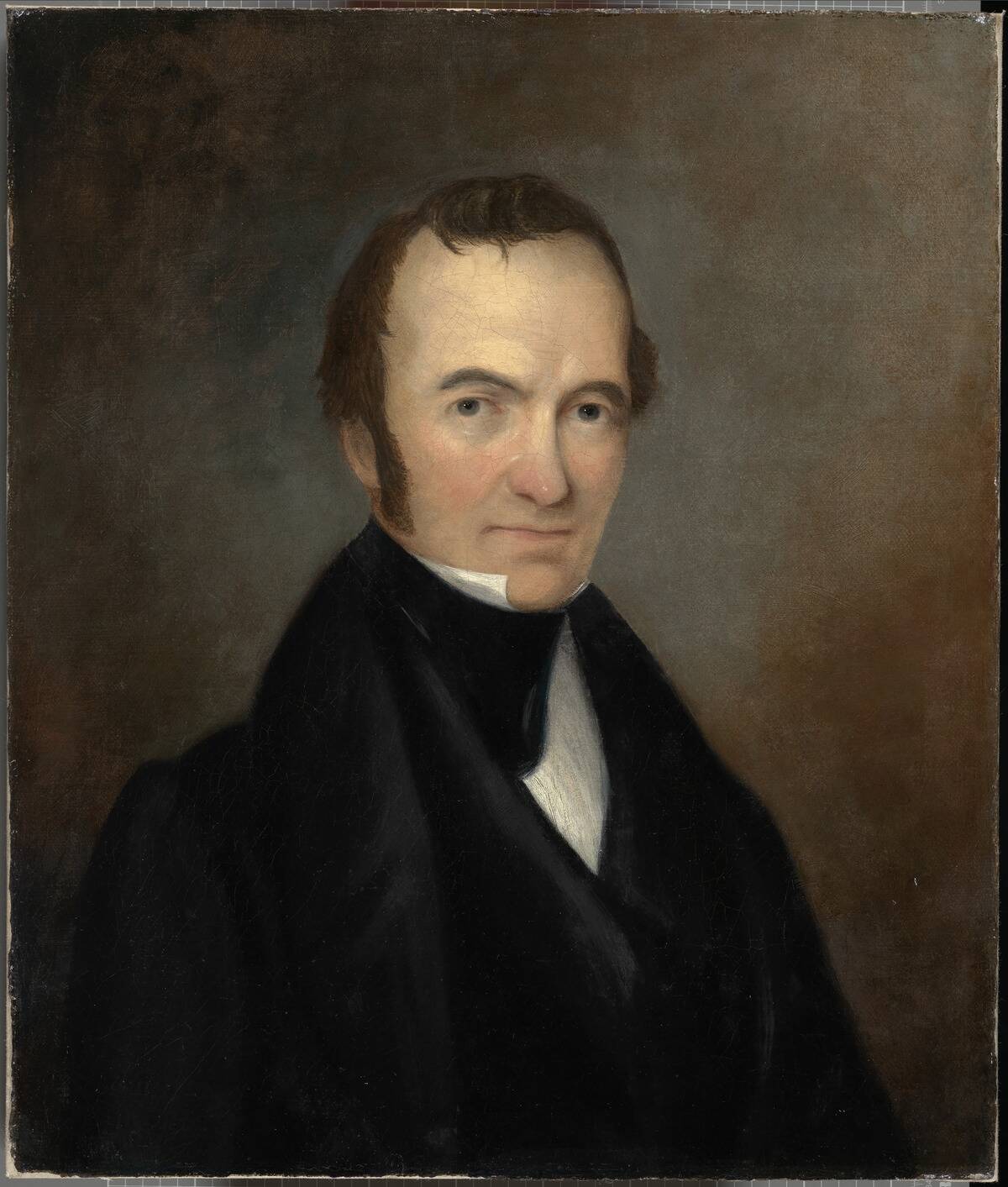

A Demographic Change Sparks A Movement

Shortly before Mexico’s independence was achieved, Spanish authorities allowed Stephen Austin and about 300 families in his company to settle in San Antonio. They would arrive in the summer of 1821.

This move marks one of the reasons Austin is considered the “Father of Texas,” and it encouraged further American citizens to make similar journeys to Texas over the following decades. Together, they would increasingly push for Texas’s independence from Mexico.

The Start Of The Texan War Of Independence

This revolutionary movement would escalate in December 1835, when a group of volunteers led by George Collinsworth and Benjamin Milam overwhelmed the troops stationed at the Alamo.

Once the fort fell, the rebelling Texans were able to seize control of the San Antonio settlement itself. Friend and foe alike would soon descend on the former mission.

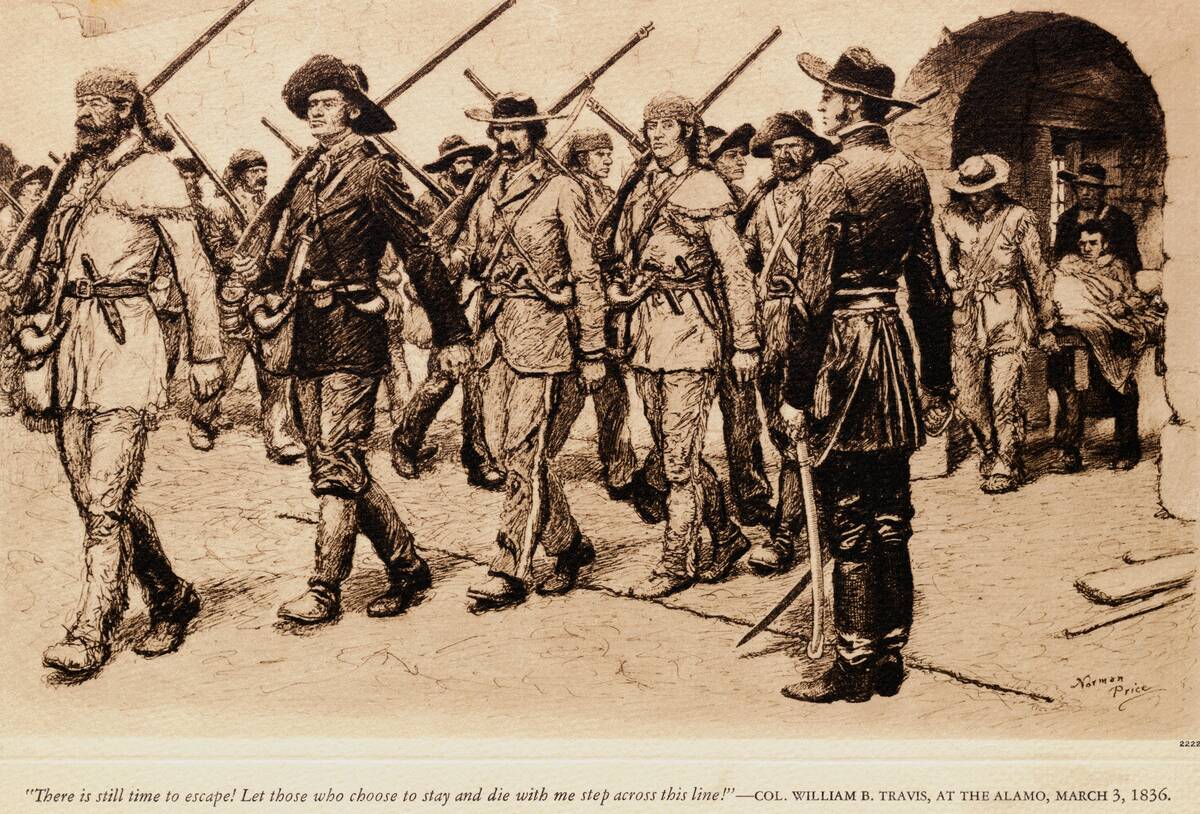

The Defenders Attract Distinguished Military Leadership

By February 1836, the Texan rebels would find dedicated, experienced leaders who took command of their efforts to defend the newly-captured Alamo.

In this artist’s rendering, one of them — Lieutenant Colonel William B. Travis — can be seen leading a company of the defenders as they underwent marching drills.

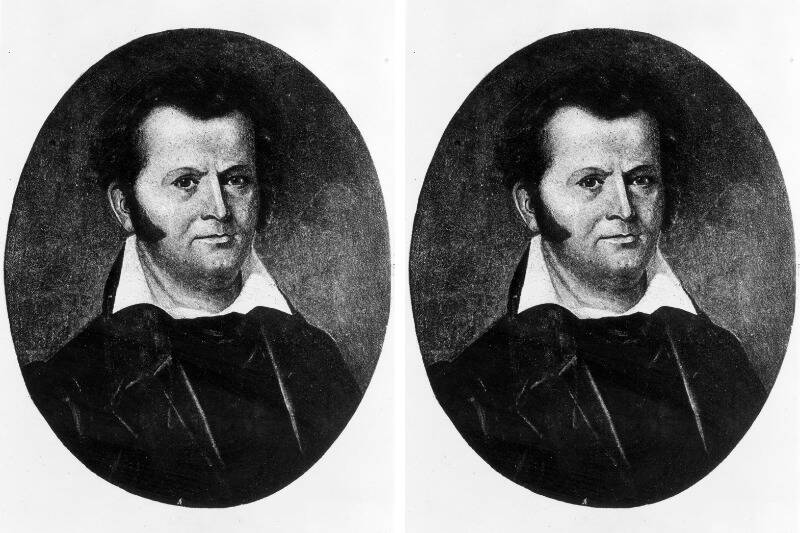

The Commander In Charge

However, the highest commanding officer present at the Alamo was Colonel James Bowie, who was famous for wielding the signature large knife created by his brother Rezin.

Although the commander-in-chief of the revolutionary Texan forces — Sam Houston — advised abandoning San Antonio due to sparse troop numbers, Bowie, Travis, and the men who first took the Alamo put their lives on the line to defend it.

Davy Crockett’s Reinforcements From Tennessee Arrive

Around the same time that Travis and Bowie arrived, legendary frontiersman and former congressman and Tennessee militia fighter David Crockett traveled to San Antonio with enough volunteers to bring the total forces defending the Alamo to 200.

Nonetheless, it was clear that even the bolstered Alamo defenders had a slim chance of holding out against the much larger Mexican army detachment.

The Fighting Didn’t Start Immediately

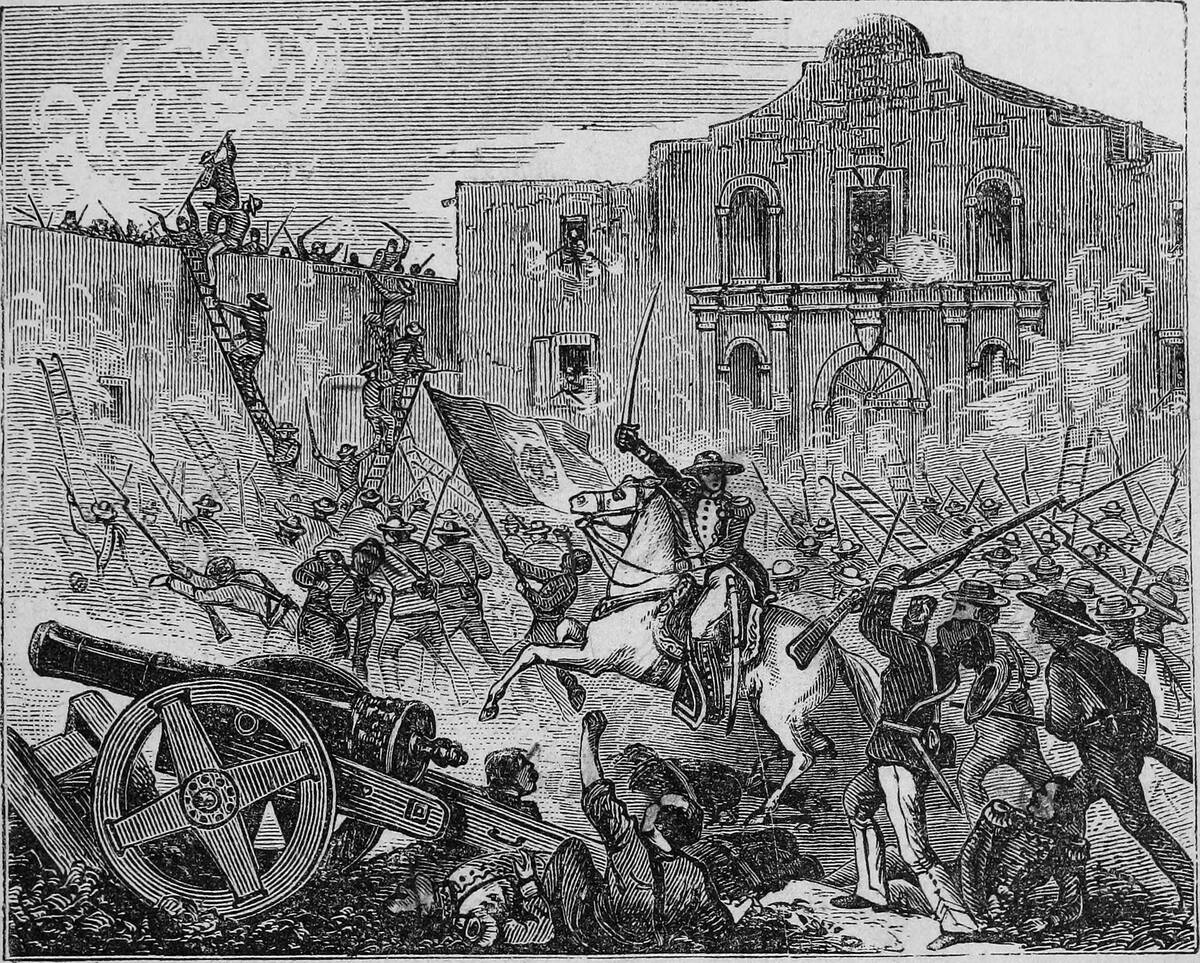

On February 23, a Mexican force that numbered at least 1,800 men but potentially included as many as 6,000 arrived in San Antonio under the command of General Antonio Lopez de Santa Anna.

After surrounding the Alamo, they laid siege to it for 13 days. In that time, gunfire was exchanged and the Mexican forces set up artillery, but few casualties fell on either side.

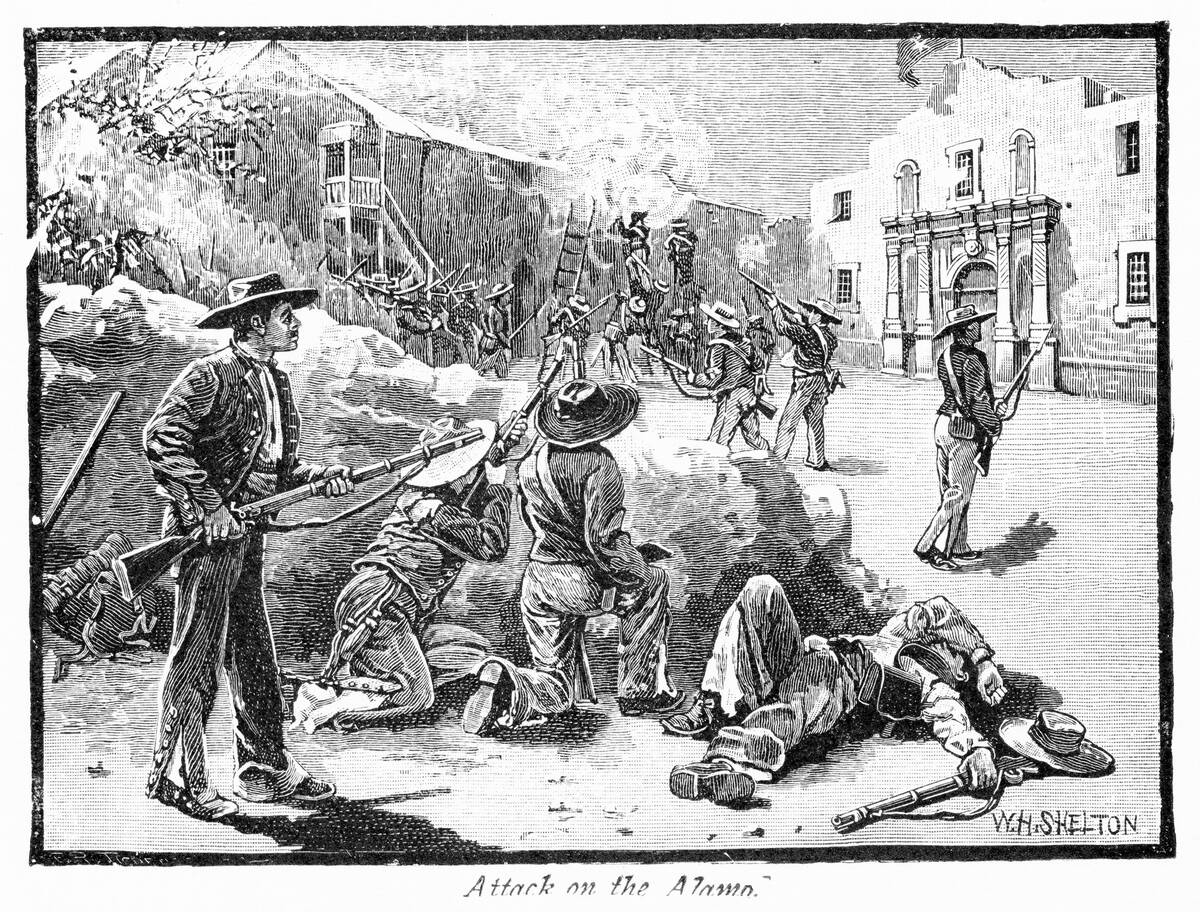

The Mexican Army Breaks Through

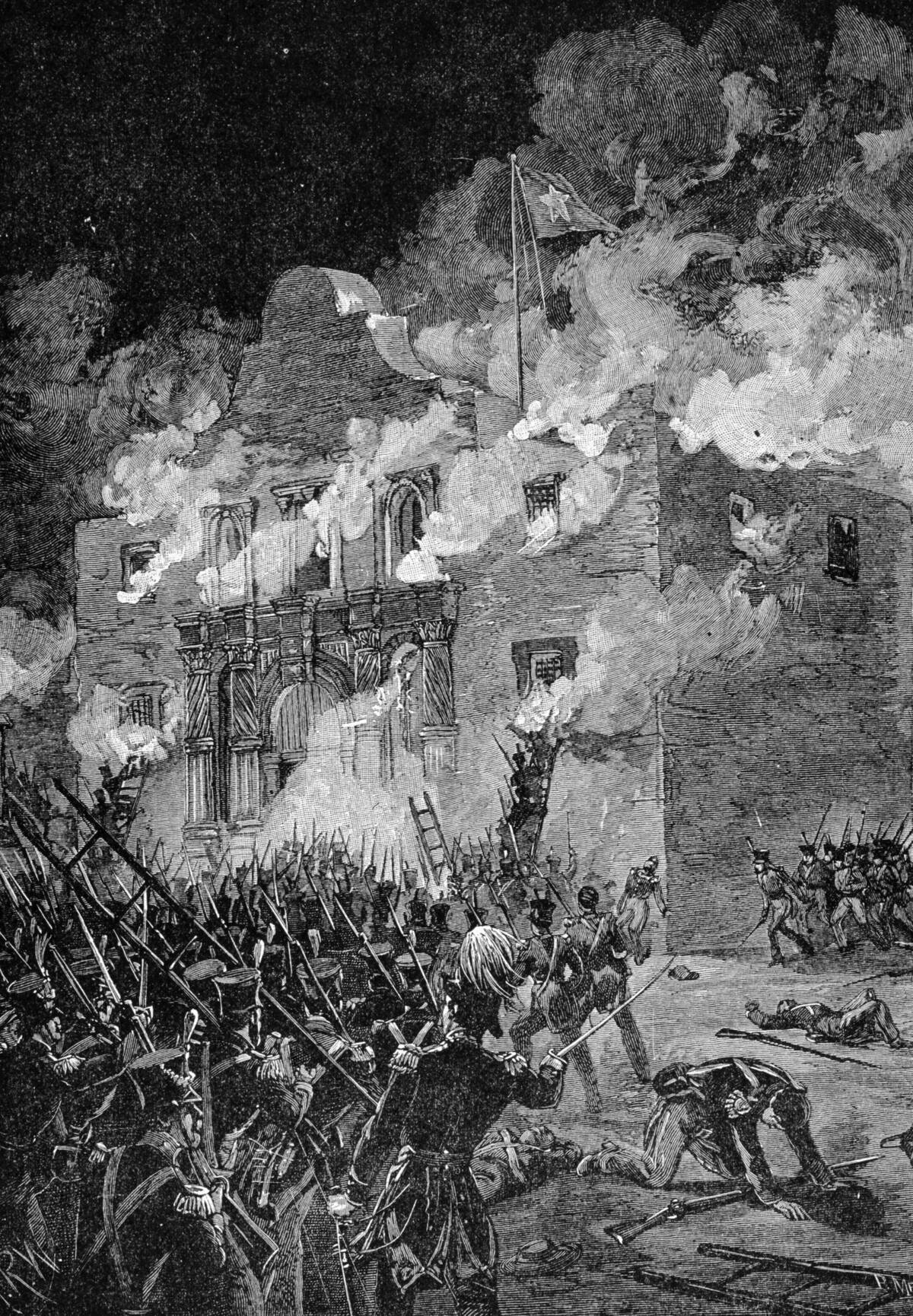

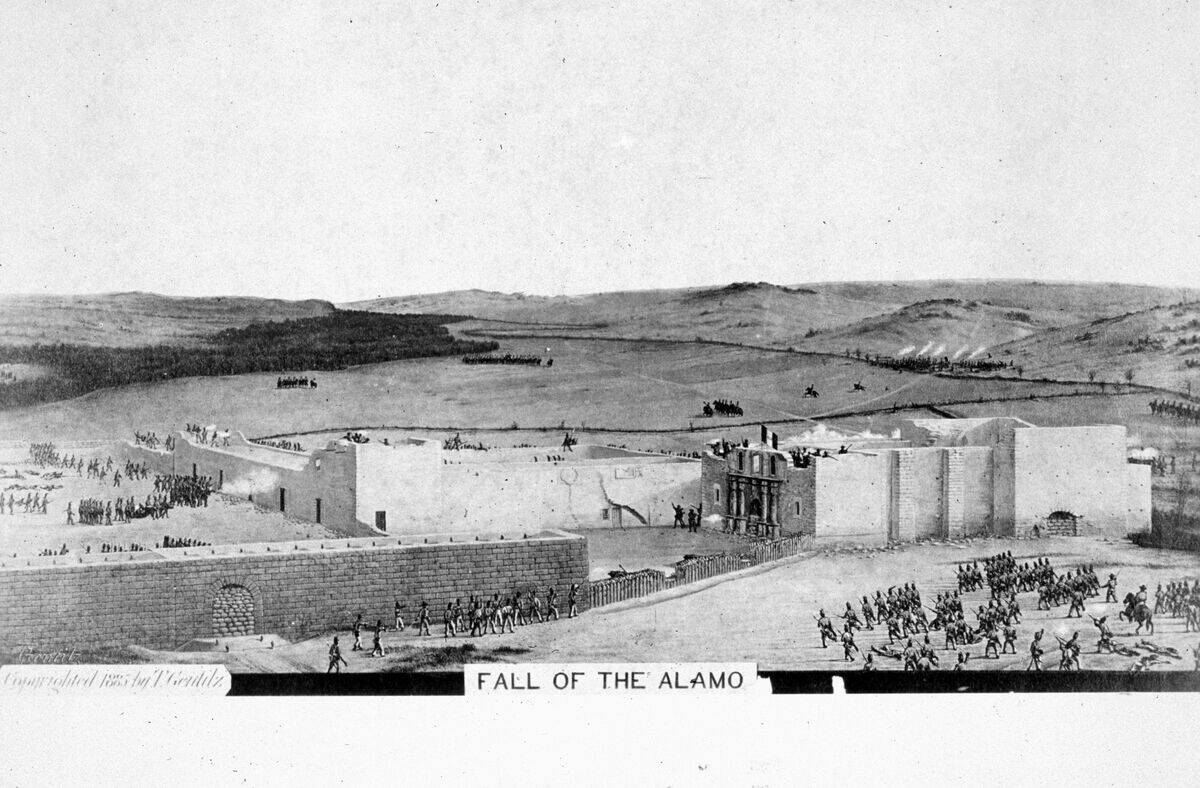

Despite how steadfastly the Alamo defenders held out, Mexican forces were eventually able to break through the fort’s north wall on March 6, 1836.

Since the ensuing attack came before dawn, many of the Texans inside were awakened by the breach. Nonetheless, they still fought back as troops flooded in through the hole.

Bowie Had Already Been Hampered By Illness

Although this artist’s rendering depicts Colonel Bowie fighting bravely to the end, he’s not just shown in bed because he was caught by surprise.

Instead, he had been relieved of his command and placed on bed rest on February 26 due to a debilitating illness that the few doctors at the Alamo weren’t able to diagnose. Although reports of his death severely conflict, the most widely-accepted of them is that he engaged the enemy with his pistols from bed.

Crockett Was Smeared After His Death

Although there is conflicting evidence regarding Crockett’s fate as well, reports suggesting that Crockett surrendered only to be executed later were not supported even by many of General Santa Anna’s staff.

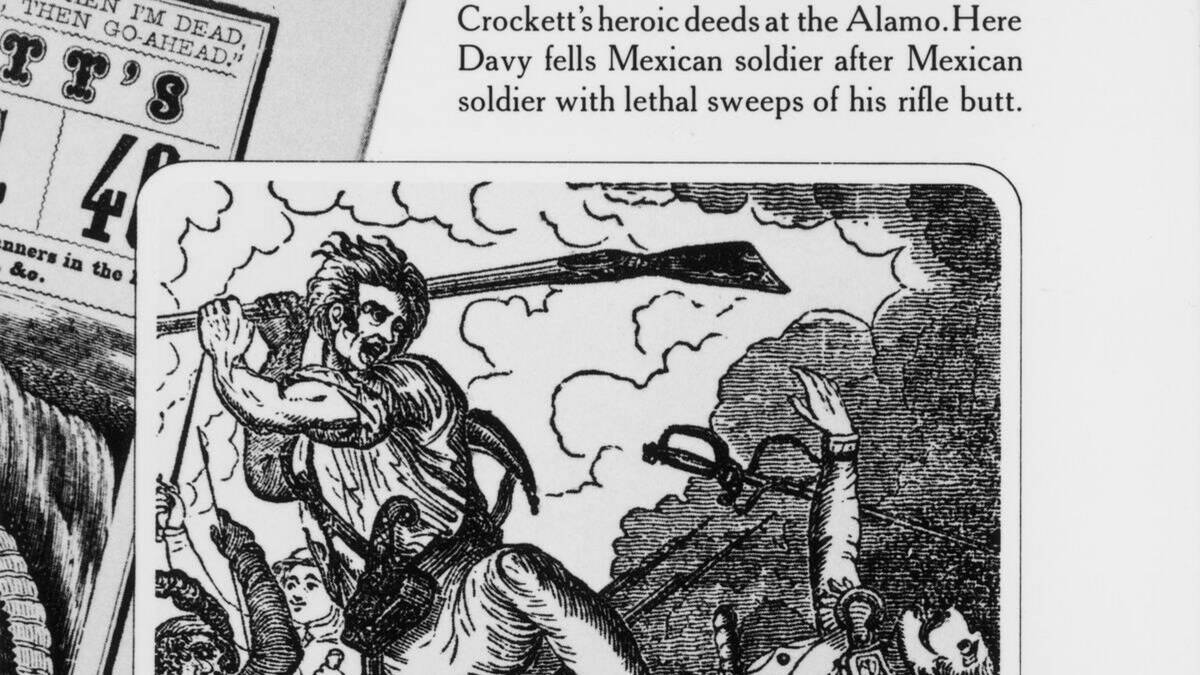

Thus, depictions of Crockett’s final moments at the Alamo show him bravely fighting until Mexican forces claimed his life as well, as survivors of the battle described him doing.

A Particularly Vivid Account Of Crockett’s Last Stand

This artist’s rendering of Crockett depicts him getting close enough to attacking Mexican troops to club them with the butt of his rifle. Although its unknown whether he actually fought that way, his proximity was confirmed by a formerly enslaved man named Ben who acted as a cook for one of Santa Anna’s officers.

According to Lon Tinkle’s book 13 Days to Glory: The Siege of the Alamo, Ben asserted that Crockett’s body was found in a barracks and surrounded by the remains of 16 Mexican troops, one of whom still had Crockett’s knife sticking out of him.

It’s Incredible The Battle Lasted As Long As It Did

Considering how significant certain battles throughout American history are in retrospect, it often becomes easy to underestimate how quickly they resolved.

Despite the vulnerability Mexican forces punched into the Alamo’s wall and their superior numbers, however, the 200 Alamo defenders were able to hold out for 90 minutes before Santa Anna’s troops emerged victorious.

The Road To Victory Was Paved By Heavy Losses

Although Mexican forces were eventually able to overpower the Texan defenders, the reason the battle was so protracted had to do with the staggering losses they took in the process. It’s worth remembering that they were only fighting 200 people.

Since accounts vary as to how many Mexican troops arrived at San Antonio to begin with, so too do accounts regarding their casualties. As such, anywhere between 600 and 1,600 Mexican troops could have perished during the Battle of the Alamo.

The Mexican Army Took No Prisoners

According to the History Channel, several Texans had reportedly surrendered when it was obvious to them that the battle was lost. However, it turned out that they were no better off than their comrades who had fallen in the battle.

That was because Santa Anna had ordered that all prisoners taken from the Alamo be executed. The only exceptions he made were for a handful of non-combatants.

An Allowance Typical Of The Time Period

Although everyone who fought at the Alamo met their end on March 6 one way or another, there were a small few who survived, mostly consisting of women and children.

According to the History Channel, two of them were Susannah Dickinson and her baby daughter Angelina. They were the family of Captain Almaron Dickinson, who had fallen in the battle.

Santa Anna Spared A Few For A Particular Reason

Although it’s arguable that even Santa Anna found the killing of non-combatant women and their children unconscionable, there was a more directly stated reason why he decided to let Dickinson and her daughter go.

That’s because he specifically sent them to Sam Houston’s camp in Gonzalez with a message. Through them, Santa Anna warned that if the Texans continued their revolution, they would meet the same fate as those who fell at the Alamo.

Santa Anna Leads His Troops Eastward

After the Alamo fell, the fort was once again occupied by Mexican forces. Meanwhile, Santa Anna marched an estimated 1,500 men in the same direction he had sent Dickinson earlier.

With Bowie, Travis, and Crockett slain, the biggest military thorn in his side was now Houston, who had been amassing an army in Harris County while the Alamo defenders held Mexican forces off.

Santa Anna’s Warning Backfired

Although Santa Anna had intended to spread the word of the Alamo as a cautionary tale to compel the remaining Texan forces to end their resistance, this tactic had the opposite effect.

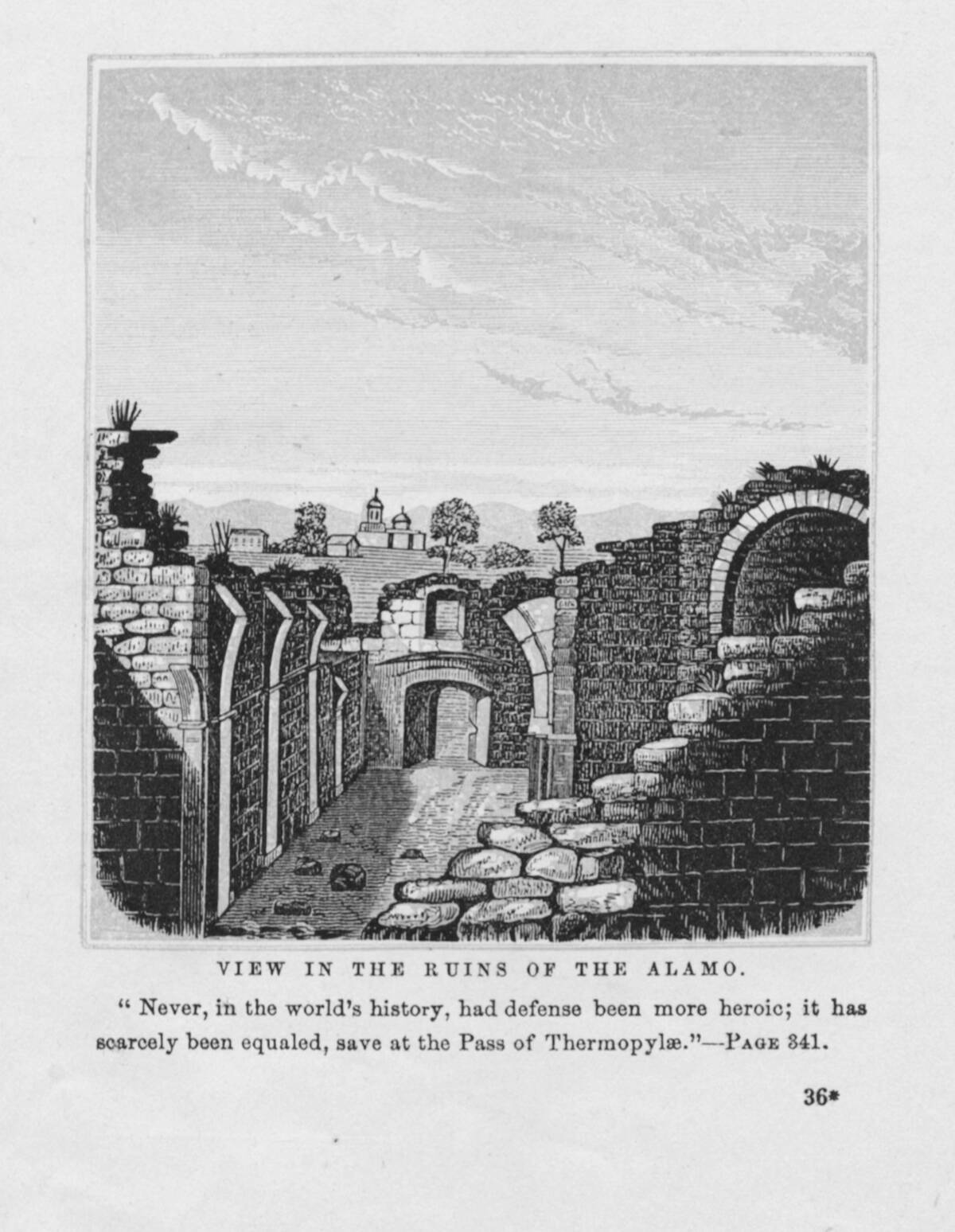

Instead, the bravery of the Alamo’s defenders — particularly Crockett — was extolled among the Texan forces and compared to the ancient Spartan Battle of Thermopylae. As such, the still-repeated phrase “Remember the Alamo” was a rallying cry to avenge their sacrifices.

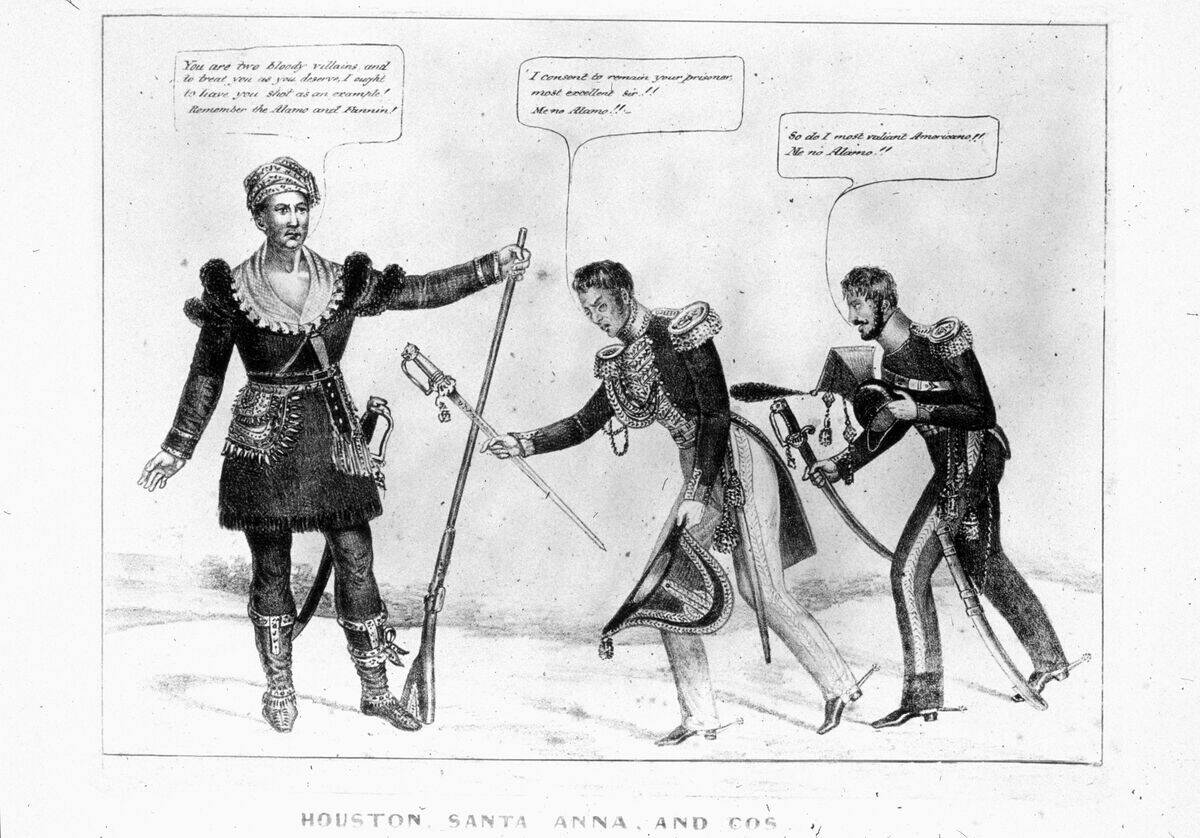

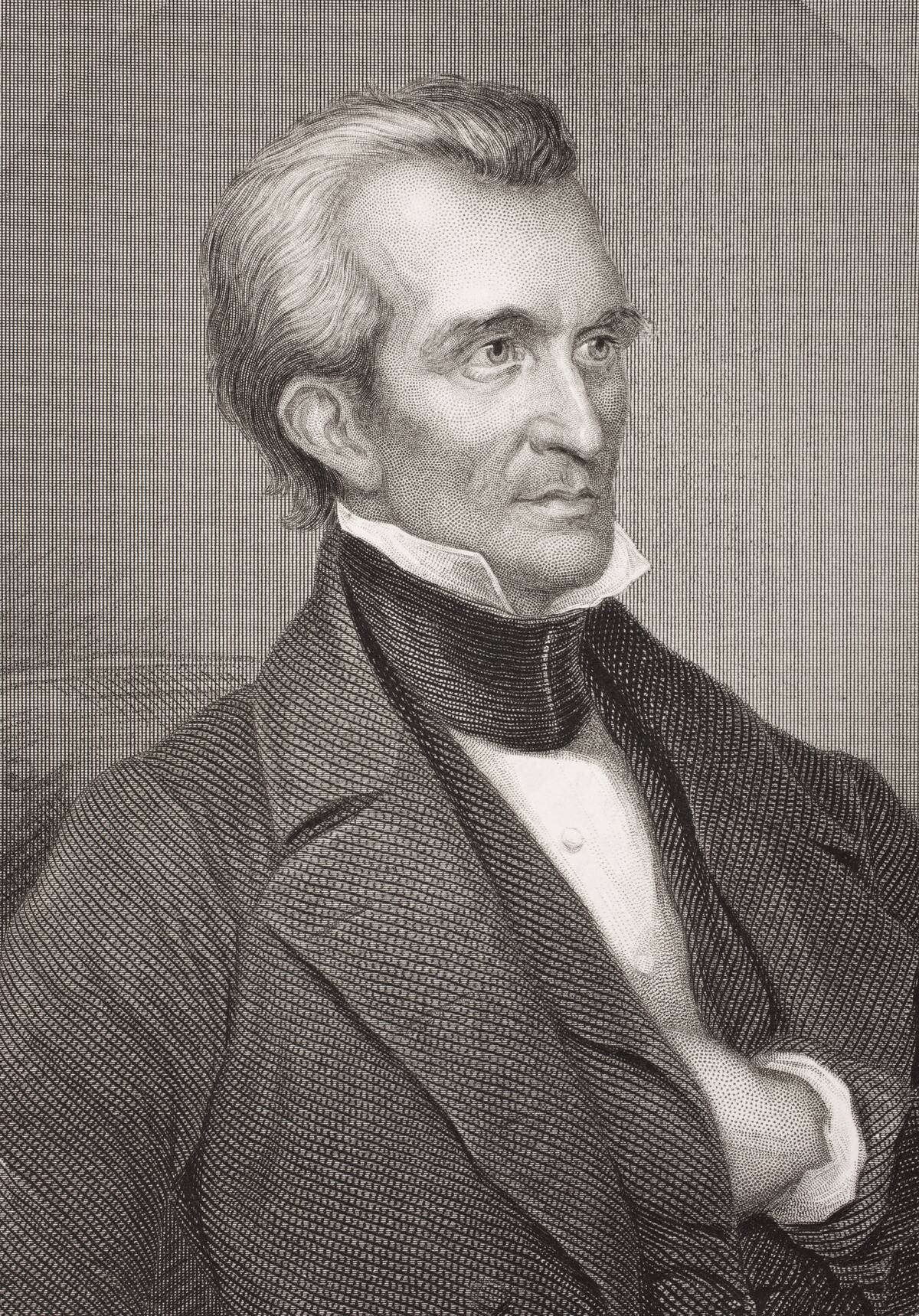

Houston Meets Santa Anna On The Battlefield

By the time Santa Anna’s forces made their way east on April 21, 1836, they were greeted by Houston (depicted at right) and his force of 800 Texans.

Although Houston’s army was four times the size of the volunteer group who defended the Alamo, they were nonetheless severely outnumbered by Santa Anna’s army of 1,500.

The Battle Of San Jacinto

Although the Battle of the Alamo was a defining battle of the Texas Revolution, the Battle of San Jacinto was just as important.

Indeed, the fighting spirit the Texan forces showed as they screamed “Remember the Alamo” during their attack was just as ferocious as the rebels they were avenging. Despite being outnumbered almost two-to-one, they emerged victorious.

More Than Just A Battle

Although one would expect Houston’s victory at San Jacinto to give his forces in the Texas Revolution, it accomplished a lot more than that. Indeed, his army was successful enough to earn Texas its independence in one fell swoop.

According to the History Channel, that was because Texan forces captured Santa Anna during the battle. As such, Texan independence was part of the terms of his surrender to Houston.

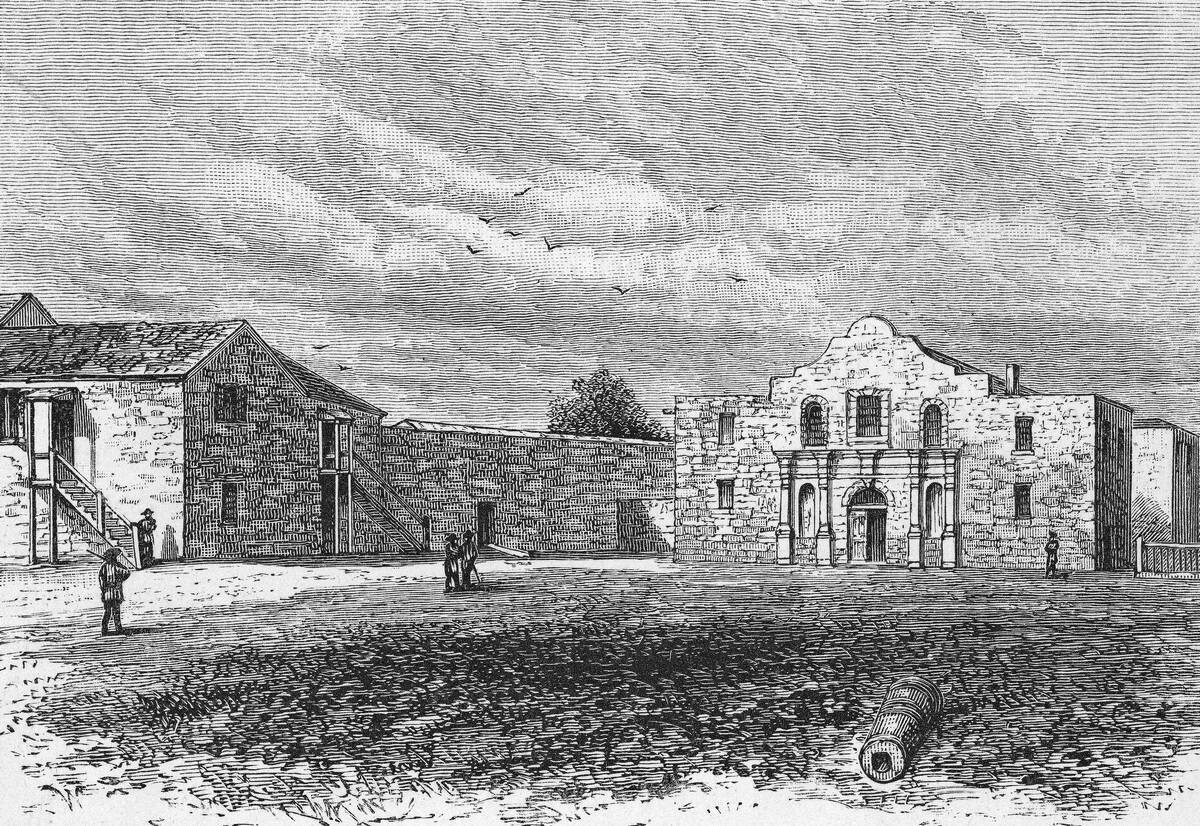

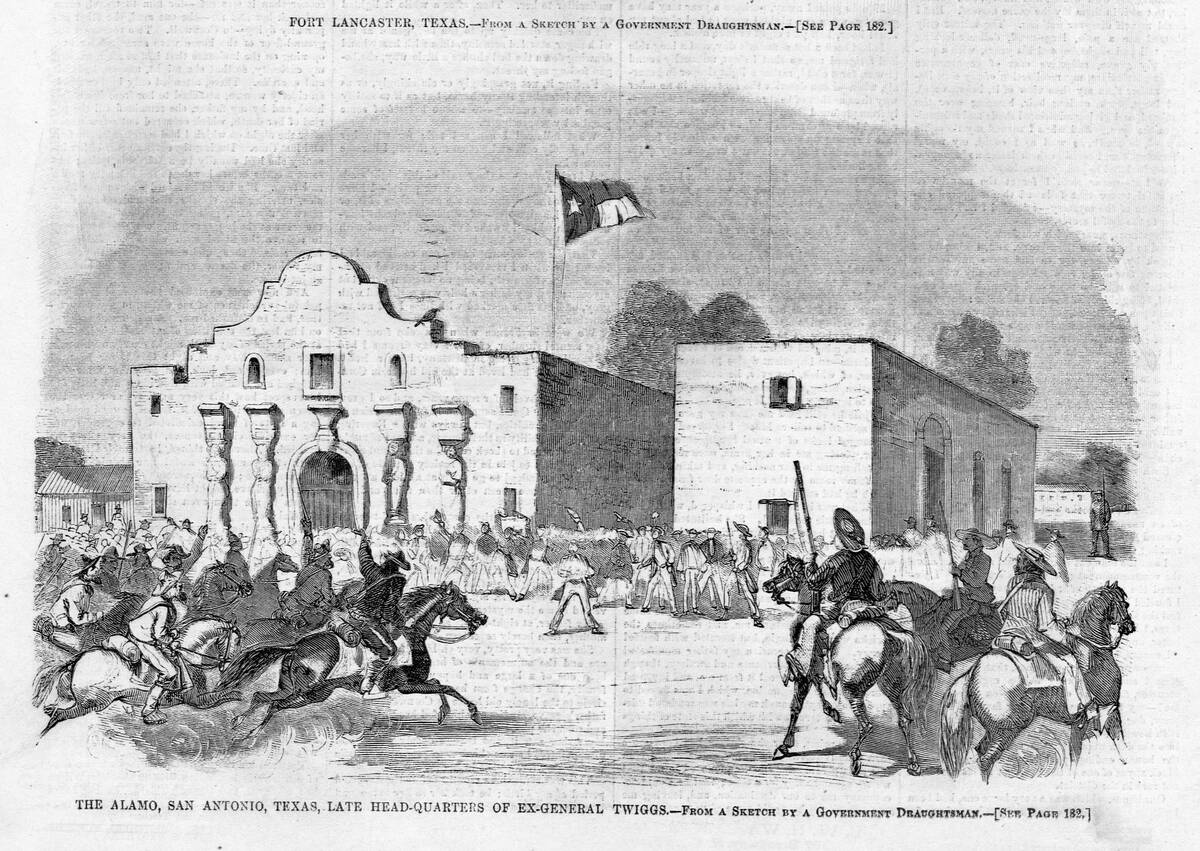

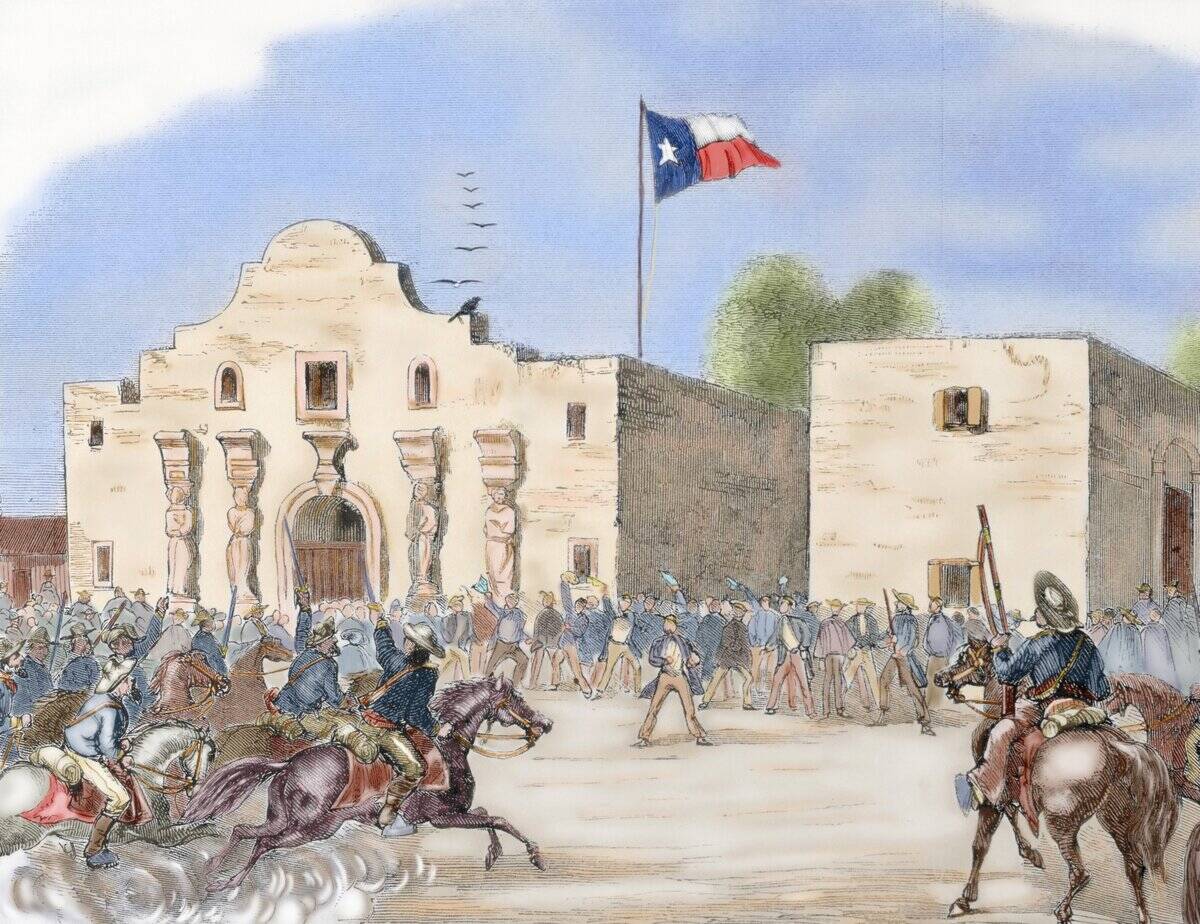

Texas Finally Gets The Alamo Back

Following Santa Anna’s surrender to Houston, Mexican troops were ordered to abandon San Antonio in May. According to the History Channel, they were also told to demolish its fortifications on their way out.

Since the former mission had already sustained damage during the battle, this artist’s rendering captures the state of its ruins by the time Mexican forces were gone in 1836. Of course, it wouldn’t look like this for long.

An Important Cultural And Military Restoration

Although the San Antonio city council allowed its citizens and tourists to purchase stones from the Alamo’s ruins for five dollars per wagon load by 1840, the fort would be completely restored before the decade was out.

As a new war loomed over Texas, the Alamo was needed both as a military fortification and as an enduring symbol of Texan morale.

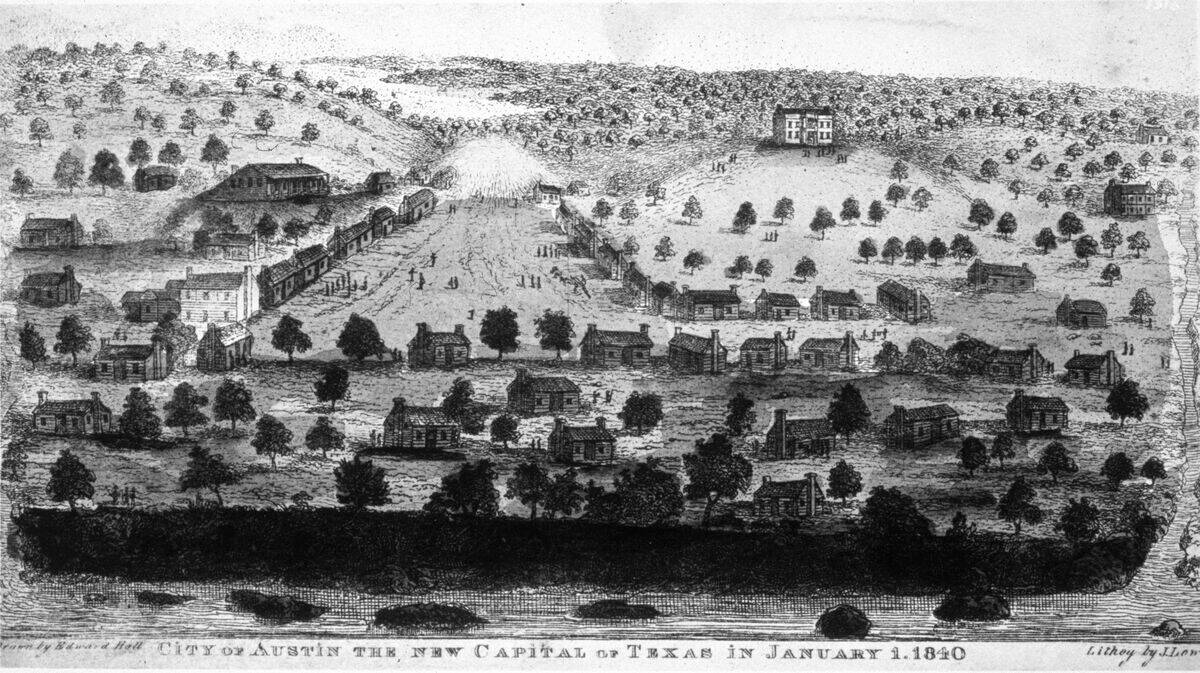

The Next Step For Texas After Independence

Although there was no shortage of Texans who wanted their new republic to join the United States after gaining independence, this sentiment was not initially echoed by the American government.

This was partially because northern states strongly opposed adding a new state that allowed slavery into the Union. Furthermore, the Mexican government had also threatened to declare war if the United States annexed Texas.

A Political Change In The Air

However, that governmental sentiment changed when President James K. Polk was elected in 1844. Although Polk’s Manifest Destiny philosophy was such that he also sought to claim Oregon, California, New Mexico, and the rest of what is now the American southwest, Texas was also a key part of his expansionist policies.

Polk had initially tried to arrange for the purchase of many of these territories but was rejected by the Mexican government.

Texas Is Officially Annexed

Although Polk began annexation procedures for Texas soon after his term began, it wasn’t until December 1845 that both the American and Texan governments formally recognized its statehood.

However, it would only take until the following year for the Mexican government to make good on its threats and attack General Zachary Taylor’s forces near the Rio Grande before laying siege to Fort Texas.

The Mexican-American War Begins

Although Taylor was able to repeal the cavalry, these actions led the American government to declare war on Mexico. Since the desired territory north of the Rio Grande had relatively few Mexican citizens in it, American forces were able to overpower many of them with relative ease.

Santa Anna returned to the fight and was even elected Mexico’s president during the Mexican-American War but resigned before the war ended in American victory with the Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo on February 2, 1848.

Why People Still Say “Remember The Alamo”

Although the Battle of the Alamo inspired the famous rallying cry oft-repeated during the Texas revolution, that wasn’t the only pivotal moment in the state’s history that modern Texans think of when they say it.

Since the Mexican-American War was fought over the right of Texas to exist as part of the United States and featured the same enemy as the revolution, American forces also used it as a rallying cry during their struggles between 1846 and 1848.