Photographs That Capture The Tragedy Of The Hindenburg Crash

Although the term “oh, the humanity” has long been a recognizable way to react to a major disaster, that only became true after radio journalist Herbert Morrison’s famous broadcast that featured him crying the phrase while witnessing one of history’s biggest aviation disasters.

On May 6, 1937, Zeppelin’s infamous Hindenburg dirigible suddenly ignited while making its final approach over Lakehurst, New Jersey, with 97 people on board. Within minutes, the entire airship was engulfed in flames as it drifted to the ground. Almost a century later, the footage and photographs of the fiery disaster remain as haunting as ever.

Why It Was Called The Hindenburg

When the Hindenburg was being constructed, Germany was going through a transitional period that saw its government change from the Weimar Republic to the regime that would go on to start and lose World War II.

According to the History Channel, the airship was named after the Weimar Republic’s final president, former field marshal Paul von Hindenburg. Since its designer Hugo Eckener despised the incoming regime, he chose Hindenburg for the craft’s namesake.

The Last Of The Rigid Airships

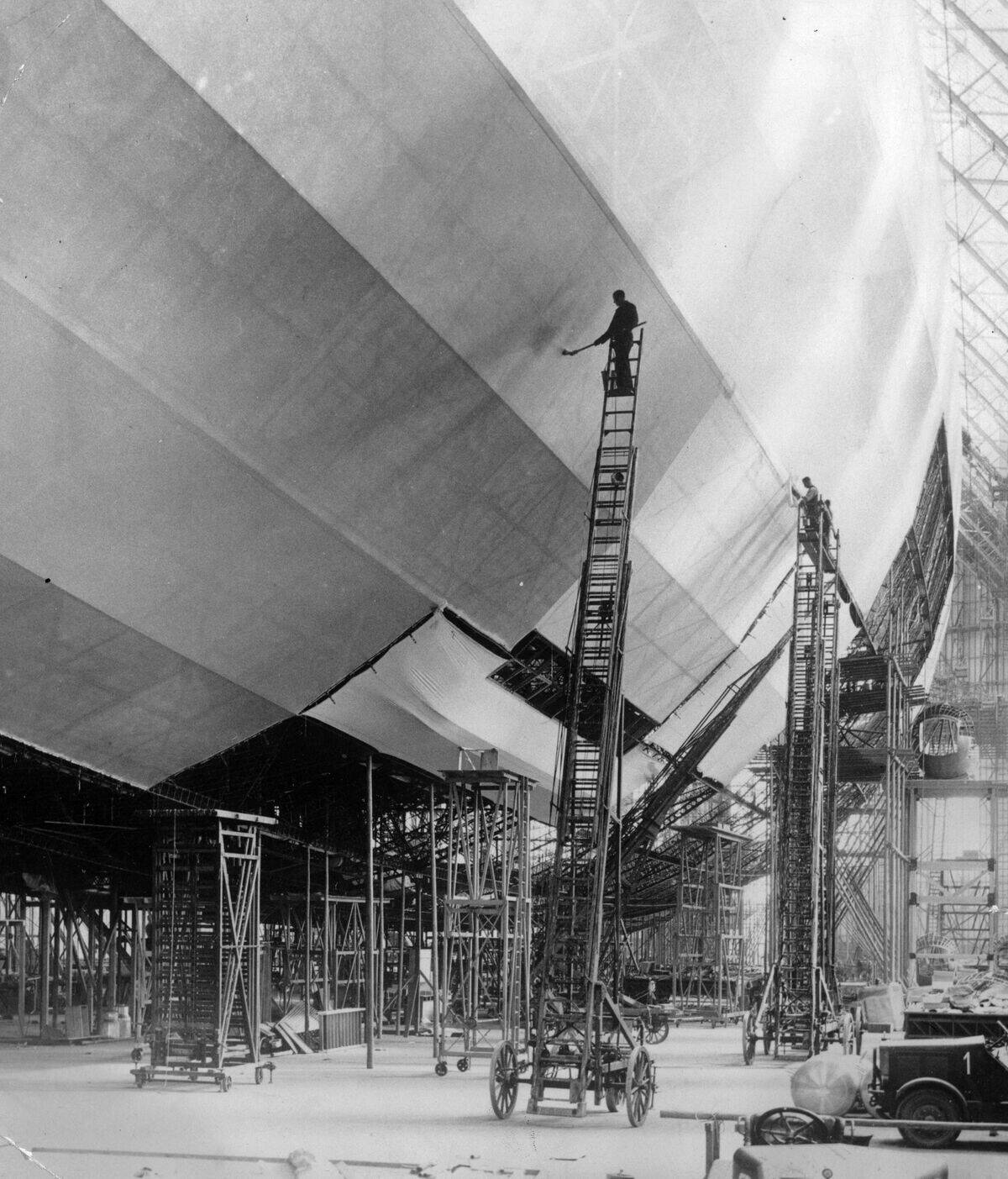

Before the age of commercial airliners when airplanes were in their infancy, it was more common to see passengers travel in giant balloon-based airships like the Zeppelin company’s famous creations. However, safety concerns inspired by the Hindenburg disaster and less famous crashes brought that era to a end before long.

Nonetheless, that doesn’t make it any less fascinating to witness the complexity of its design in this photo taken while it was still being constructed in 1934. That frame was one of the only surviving parts of the dirigible after the disaster.

The Airship’s Fatal Flaw

Although unconfirmed theories that the Hindenburg was sabotaged are as old as the disaster itself, the plausible official story blames the the fact that the Hindenburg ran on highly flammable hydrogen for the incident.

Sadly, it wasn’t Eckener’s choice to use this this ill-advised gas. According to the History Channel, he had intended to use helium but was disallowed access to the element because the United States had a monopoly on its world supply. Fearing military applications for helium, the U.S. refused to export any to Germany.

Any Further Dirigibles Never Had A Chance

Even if disasters like the Hindenburg didn’t make the world gun shy about using further dirigibles for transportation, Zeppelin wouldn’t have been likely to get the helium for safer models anyway.

Although the History Channel noted that American public opinion heavily favored loosening helium exports to Germany for its next big airship — LZ 130 — after the disaster, further geopolitical events prevented any major reform from taking place. Although U.S. law was amended to allow helium exports for nonmilitary use, the German annexation of Austria compelled Secretary Of Interior Harold Ickes not to draft any relevant contract for Germany.

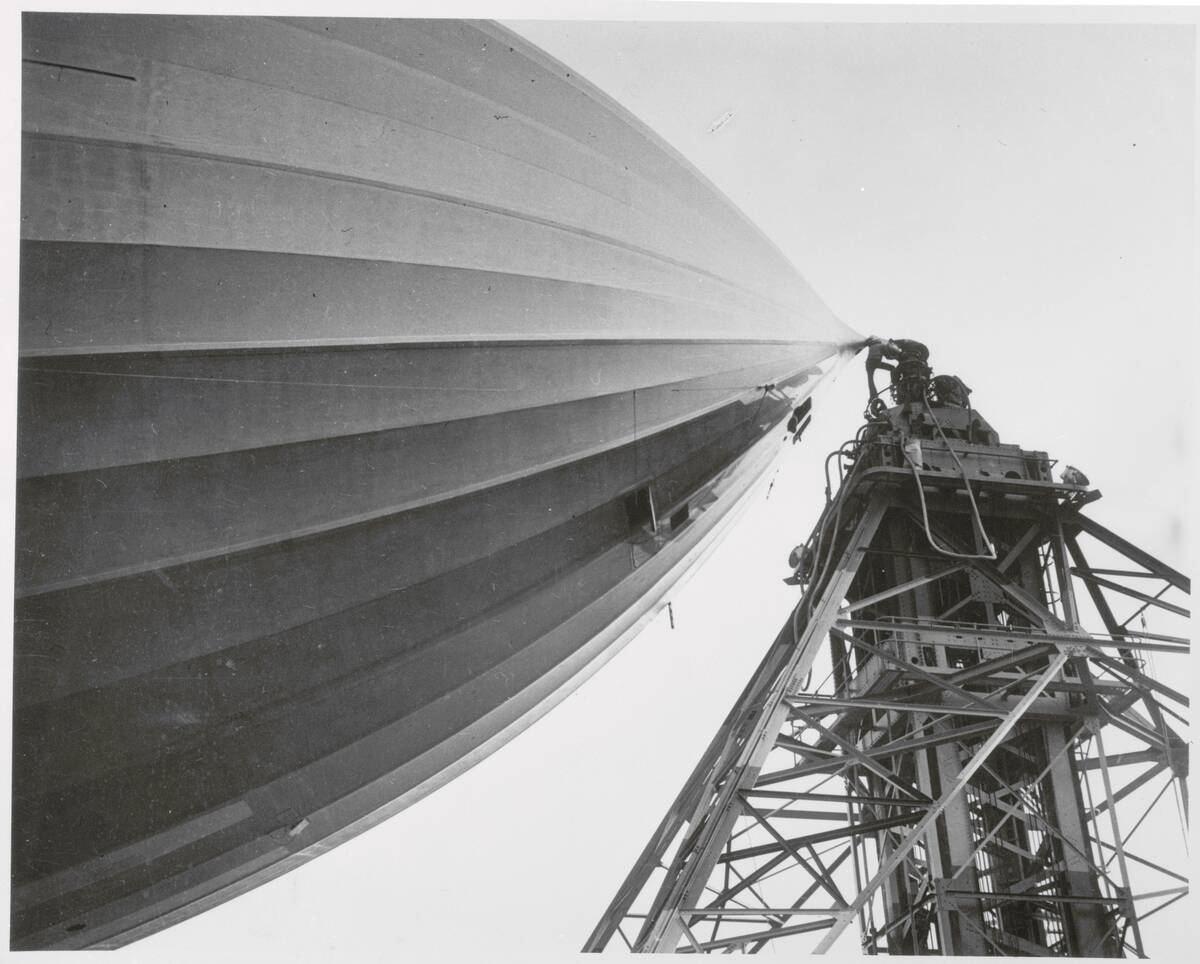

The Hindenburg’s Sheer Size

While it stands to reason that a balloon-based airship would have to be large enough to support the weight of its facilities and the nearly 100 people on board, it’s still easy to underestimate how big the aircraft actually was.

All told, the airship was 804 feet long and there’s a big difference between knowing that in the abstract and seeing seemingly tiny humans building it.

It Had A Life Before The Disaster

After the Hindenburg was built, it had its first public flight in 1936. According to the History Channel, it was used as a propaganda tool that dropped leaflets with the incoming German regime’s iconography and blared patriotic music and messages approved by Joseph Goebbels.

This propaganda flight ended up encompassing a 4,100-mile aerial tour of Germany and was specifically used to promote a referendum for the German re-annexation of the Rhineland. The referendum passed with a vote of 98.8% and the flight lasted for four days.

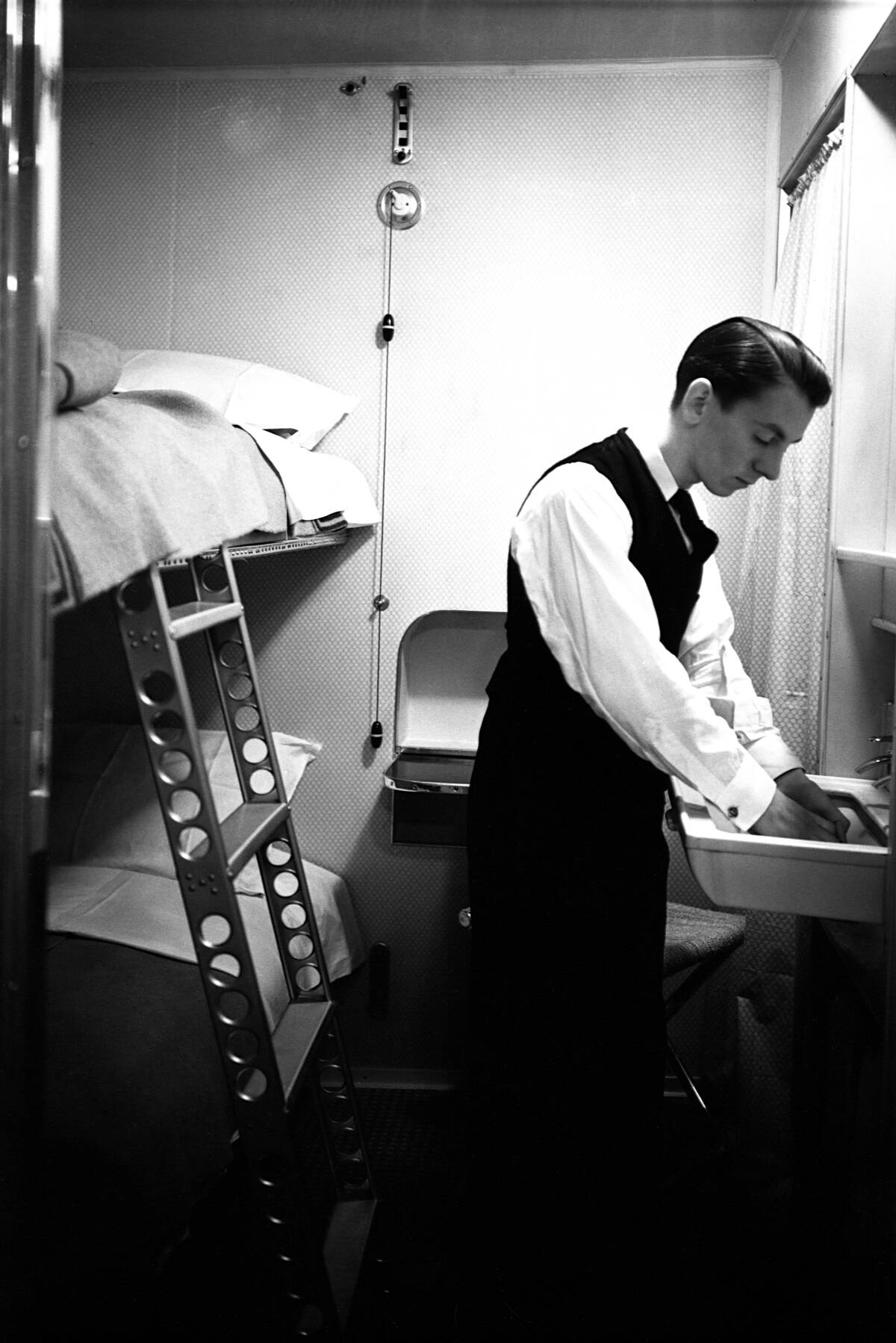

It Had Some Impressive Facilities

Although space on the Hindenburg was at such a premium to require these small staterooms, there were nonetheless some surprisingly sophisticated design decisions made to accommodate passengers. One example was a special lightweight Babygrande piano made from aluminum alloy, but that was only on its maiden flight.

In a move that seems insane given the airship’s fate, the Hindenburg also featured a smoking room. To mitigate the obvious danger here, passengers could only smoke in that room — which was pressurized to prevent hydrogen from entering — could only buy cigarettes or cigars there, and weren’t permitted to leave with any matches or smokes lit.

The Hindenburg Was At The Olympics

Some photos of the Hindenburg before its destruction show Olympic rings on its side and that’s because it made a vaunted appearance at the opening of the 1936 Summer Games in Berlin. As we can see, a photographer on board also captured an aerial view of the Olympic stadium from the dirigible.

Since it had swastikas on its tail fins, it was seen as a symbol of the regime’s power, regardless of Eckener’s intentions. It’s for that reason that the sabotage theory is somewhat plausible, as it was the subject of multiple threats to plant an explosive on the ship.

The Disaster Wasn’t Its First American Flight

Although the Hindenburg undertook its first commercial flight to Rio de Janeiro in 1936, that year also saw the ship undergo 17 Atlantic flights. Although it made a surprise visit to England in the interim, seven of those flights were scheduled for Brazil while the other ten had the United States as their destinations.

The Hindenburg can be seen flying over Manhattan in this photo but it was on its way to Lakehurst, as that was the preferred destination for each of its transatlantic flights that ended in the United States.

The Millionaires Flight

On October 8, 1936, the Hindenburg embarked on a voyage nicknamed “The Millionaires Flight” because of the prominent figures in the American and German governments, militaries, and aviation industries on board. Some notable American luminaries included future New York governor and American vice president Nelson Rockefeller and World War I flying ace Eddie Rickenbacker.

Those aboard would have had access to this (at the time) state-of-the-art reading and writing room, which featured lightweight metal furniture and a surprisingly spacious design.

A Close Look At The Control Room

Although it’s often hard to notice when observing a massive, impressive-looking airship, the most important part of a dirigible like the Hindenburg is the little cabin at its bottom.

That’s the control room, which likely wouldn’t need to be said when looking at this photo. After all, the men standing around in officer’s uniforms did a good job of conveying thst all on their own.

The Fateful Night

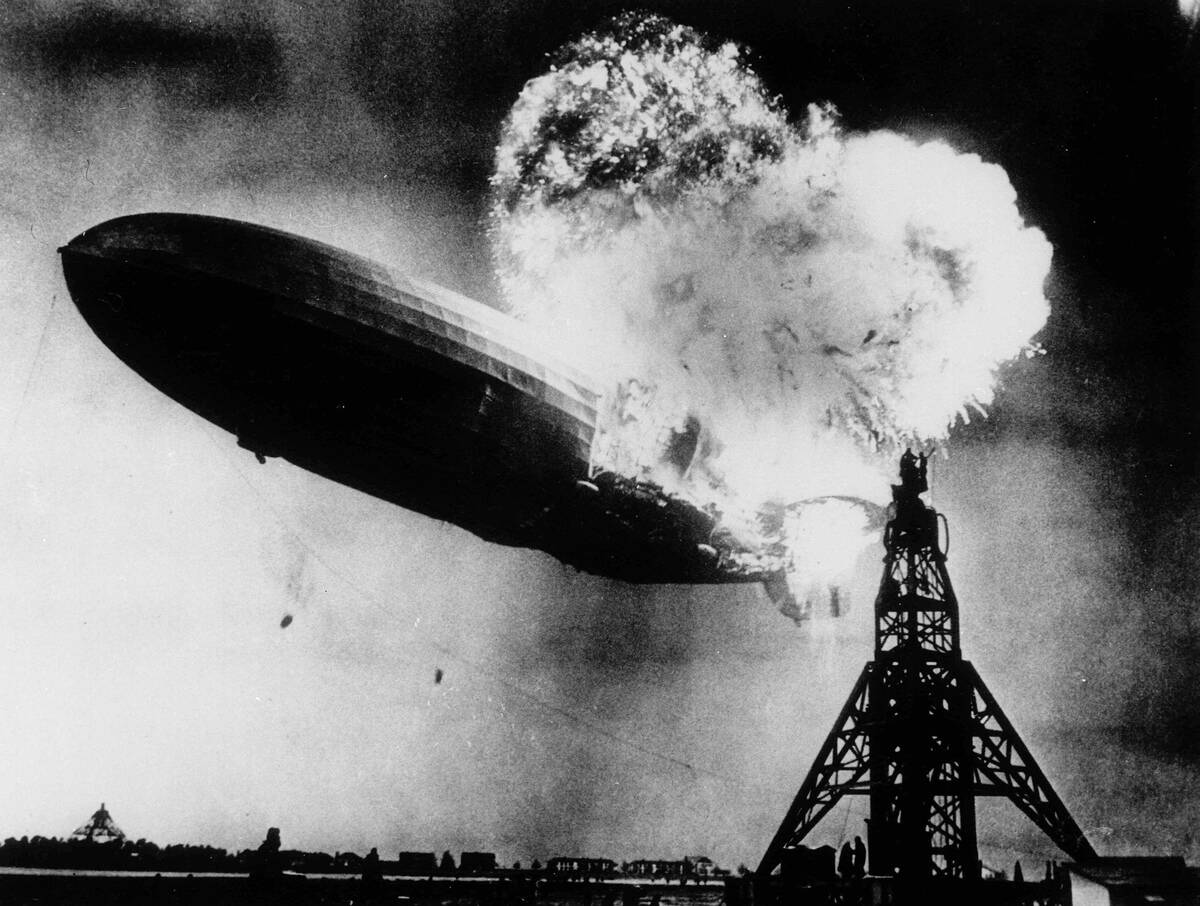

After delaying its landing for several hours due to thunderstorms, the Hindenburg made its final approach to Lakehurst on the evening of May 6, 1937. As Captain Max Pruss commanded the vessel, it made this approach at an altitude of 660 feet.

At 7:21 pm that night, two landing lines were dropped from the airship and retrieved by ground handlers. Four minutes later, the Hindenburg suddenly burst into flames.

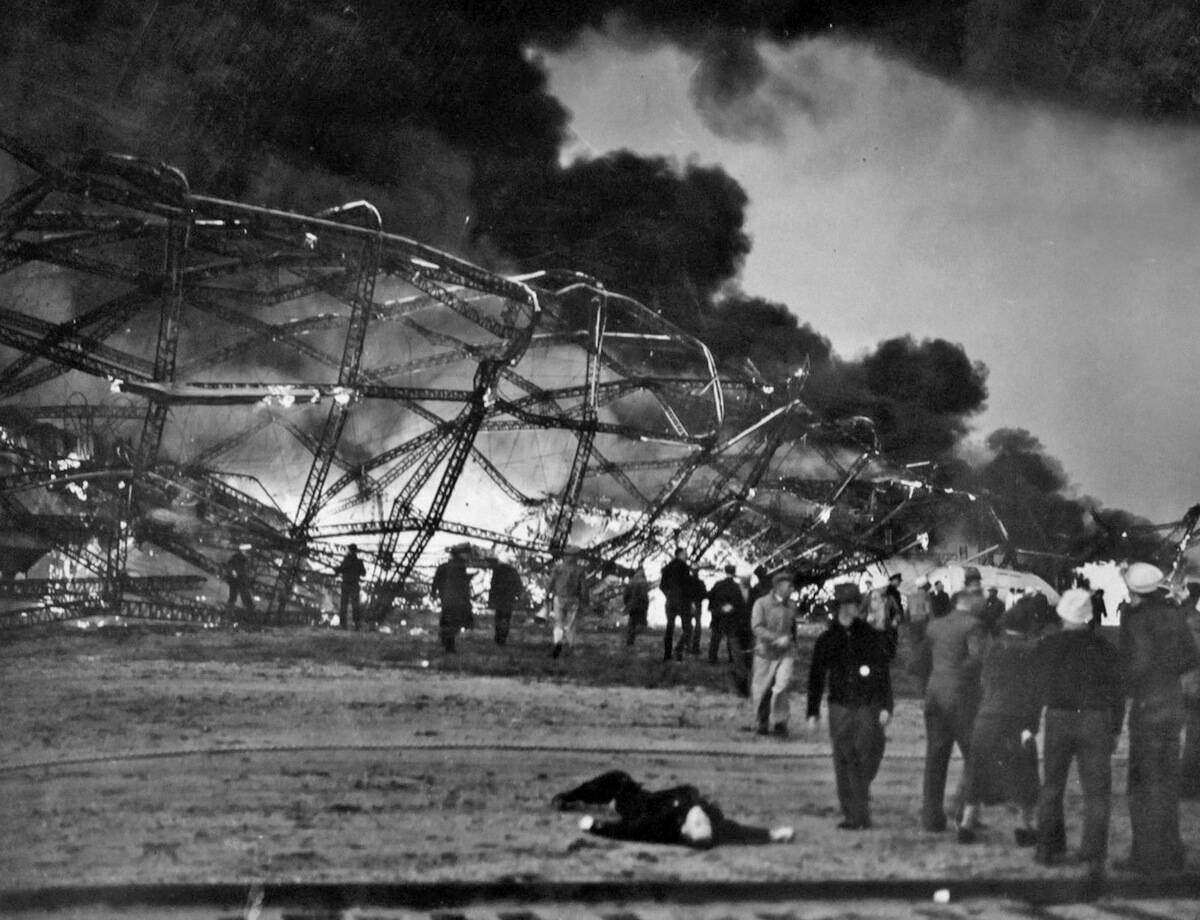

It Went Down Surprisingly Quickly

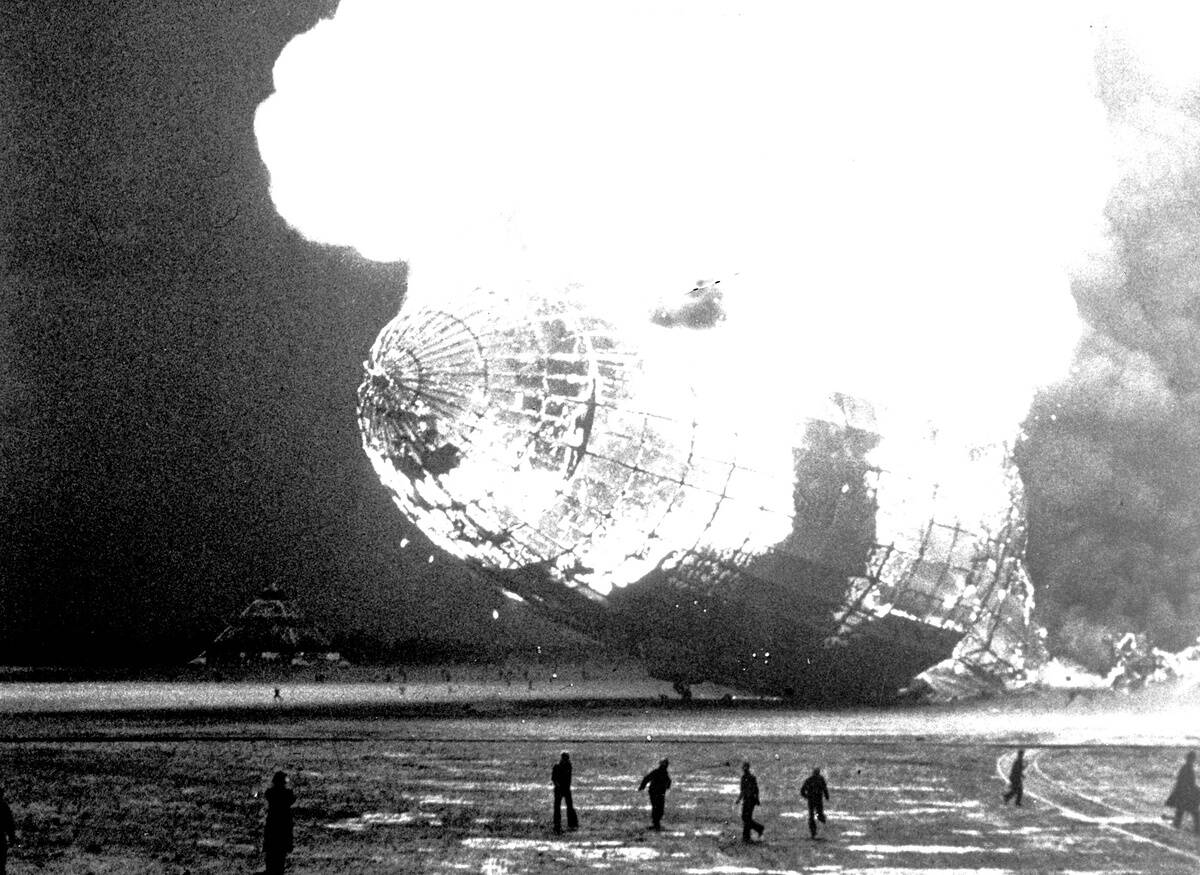

In this photo, the Hindenburg’s twisted frame can be seen burning on the ground as people either look on in horror or collapse from exhaustion. However, it’s worth noting that this photo was only taken minutes after ones showing the airship aloft as it burns.

That’s because after the airship first ignited at 7:25 pm, it only took just over half a minute to fall to the ground.

Not As Terrible As It Looks

If someone were to only to see the footage of the Hindenburg burning up, it would be reasonable for them to think that everyone aboard must have perished. After all, there wasn’t an inch of the aircraft that wasn’t engulfed in flames by the time it touched the ground.

However, the unbelievable truth about the incident was that the vast majority of passengers actually survived the disaster.

A Terrible Toll Even If It Could’ve Been Worse

Despite the the fact that there were far more survivors than the footage of the incident would suggest, the Hindenburg crash was still a certifiable disaster that claimed dozens of lives.

Specifically, 36 out of the 97 people on board lost their lives. This included 13 passengers, 22 crew members, and one of the ground handlers.

The Reason For The 62 Miraculous Survivors

There were multiple factors behind the impressive luck on the side of the Hindenburg’s survivors and while there was no good time for the hydrogen inside the balloon to ignite, it’s also true that the least disastrous time for this when it was already in the process of landing.

This allowed survivors to jump from the Hindenburg’s many promenade windows and those in the control room without falling to their deaths. Most survivors were also on the ship’s A deck at the time, which was the closest to these windows and the ground.

The Location Was Also A Factor

Those who survived also couldn’t have chosen a better place to experience an incident like this, as the disaster response of the Navy personnel at the Lakehurst Naval Air Station undeniably saved lives.

In particular, the leadership of Chief Petty Officer Frederick J. “Bull” Tobin was significant to the rescue effort, as his men instinctively ran from the disaster before he shouted, “Navy men, stand fast!” Once they did, they were able to come together and bravely rescue fleeing survivors.

The Aftermath

Although many Hindenburg survivors understandably experienced severe burns, some were luckier than others.

Although this crew member was in traction as he read about the disaster from a Philadelphia hospital, it would appear that a relatively small portion of his body — if any — was burned. Compared to others, he may not have been in the hospital for long.

Few Conclusive Answers To Be Had

While the hydrogen used to power the dirigible was certainly a catalyst for the severity of the disaster, it’s still a subject of intense debate as to how the fire started in the first place.

Those photo captures in inquiry in session to determine the disaster’s unanswered questions but since some of the event is still shrouded in mystery, it wasn’t able to address every lingering question.

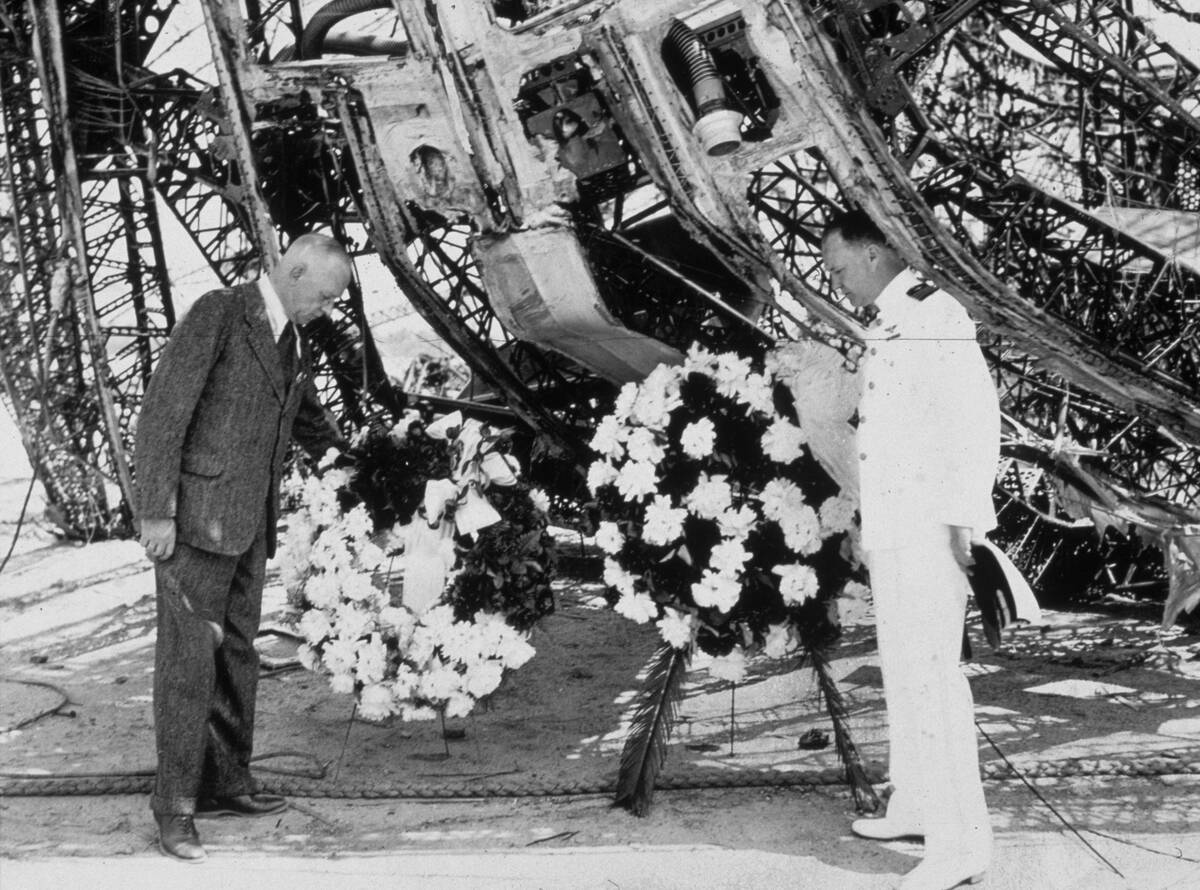

A Time Of Mourning And A Meeting Of Officers

Once the dust had settled on the disaster, Lieutenant Colonel Joachim Breithaupt of the special German commission (left) met with the Lakehurst Air Station’s representative — Commander Charles E. Rosendahl — to lay their respective memorial wreaths on the Hindenburg’s bow.

Four years later, their respective nations would be at war.